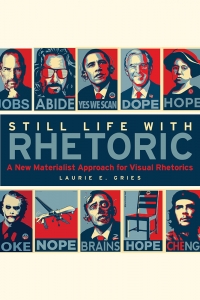

Still Life With Rhetoric:

A New Materialist Approach for Visual Rhetorics

By: Laurie Gries

Review By: Angelia Giannone

Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2015

ISBN: 978-0-874219777, 336 pages.

|

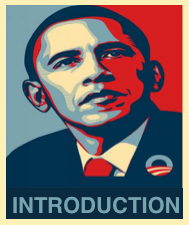

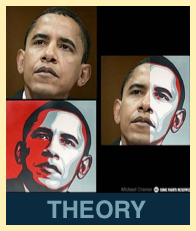

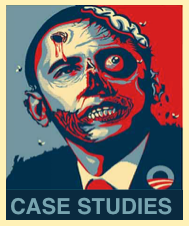

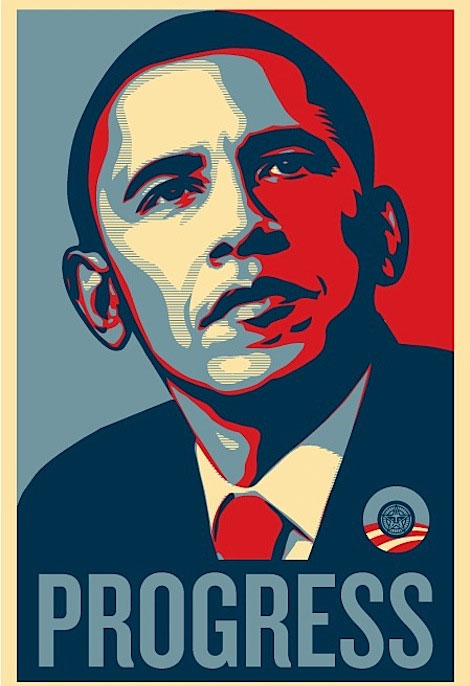

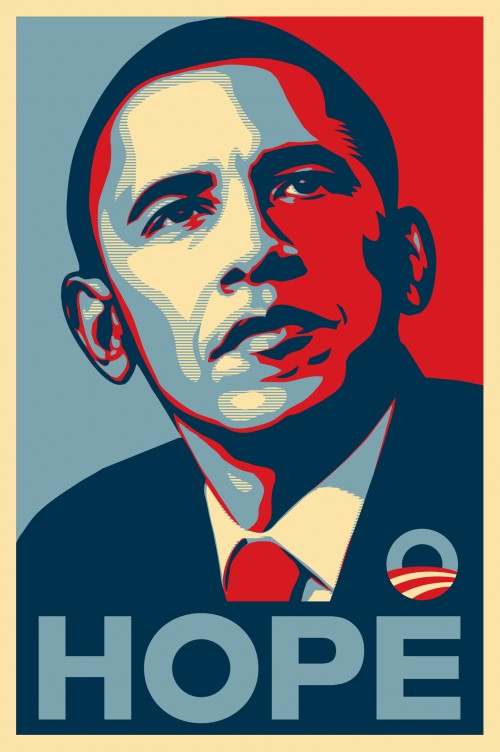

Introduction: Overview and the Obama Hope Image Overview With Digital Age technology, researchers are finding that some traditional methods for studying print, analog, or simply nondigital images or texts no longer suffice. This is further amplified with the advent of the Internet and global communities that allow information to rapidly circulate and morph. As such, Laurie Gries’s 2015 monograph Still Life With Rhetoric: A New Materialist Approach for Visual Rhetorics presents a pleasantly thorough and much needed research method of habitus for (digital) visual rhetoricians: iconographic tracking (pp. 106–32). Iconographic tracking, as Gries first explains and then shows through her Obama Hope image case study, provides both the mentality as well as a tangible, action-oriented way for scholars to track and document the life—and therefore evolution—of images, focusing on their rhetorical essence. Through iconographic tracking, Gries argues that the lives and evolutions of images can be traced and recorded and that images and their contexts can thus be subject to rhetorical analysis broadly. She illustrates the ability and need to study images in this way through four case studies of the Obama Hope image. With these case studies, Gries draws from various social, political, artistic, and judicial (to name a few) events and cultures, and she subsequently provides rhetorical analyses based on factors surrounding specific instances of the Obama Hope image’s life—its history, artistic form, controversy, satirical memes, and so on. Obama Hope Image

The Obama Hope image was first created by Shepard Fairey, street artist and activist who founded Obey Giant. As Gries explains, the original photograph of Obama was taken by Mannie Garcia for the Associated Press (AP) (p. 181), and that Fairey found the image by a simple Google search without considering copyright and fair use issues that would later come into question (p. 178). Fairey first created a Progress image that evolved into Hope to rally support for Obama's 2008 presidential campaign (p. 143). All sale proceeds from official products made by Fairey or events he hosted went toward Obama's campaign, and soon the Obama Hope image became the face of Obama's campaign (p. 144–49). About one year after Fairey made the image and it became popularized in the media, the Associated Press sued Fairey for using Garcia's photo, and the Obama Hope image soon became a catalyst for controversies surrounding fair use, copyright, and art activism (p. 181). Once the image became popularized, many image editing websites began to offer Obama filters for users to transform their own images into the style of the Obama Hope image, such as OBAMA-ME, LunaPic, and Obama Poster Maker. |