Disrupting with littleBits: An Automated Study Station that Purposefully Fails

In her Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) Chair's Address, Joyce Carter (2016) concluded by giving the field a charge: "Go forth and innovate. Disrupt. Make. Reframe," adding, "Conserve what’s worth conserving and jettison the rest in the name of creative destruction" (p. 405). Carter's words influenced and shaped our group discussions and practices each day as we worked on this project. Disruption became one of the fundamental frameworks informing our decisions as we composed with littleBits. littleBits kits come with instruction sets with directions on how to build pre-designed inventions (e.g., a remote control car, a disco ball-style lamp, a throwing arm). Users of littleBits could easily play safely and follow the instructions to create readymade assemblages.

But how does one disrupt something like littleBits that comes with those kinds of instructions? As standardized, mass-manufactured objects, littleBits constrain invention practices in that the politics of their design limit options. However, as commonplaces, they can also be assembled in new and unpredictable ways, and they can be combined with other commonplace three-dimensional objects for new inventions. Indeed, this functionality is a motivation for using littleBits. As littleBits founder Ayah Bdeir (2009) has touted, they allow for "a democratization of electronics" (p. 397). In this section, we explain our praxis inventing with littleBits to create an invention that purposefully fails. As we show, this inventional process was one of discovery rather than simply convention (Hammer & Knight, 2015) in which we remixed the commonplace inventions of littleBits into an assemblage. In this way, we show how three-dimensional, mass-produced commonplaces can be assembled into new inventions that are representative of craft, the sort of composition that Anne Frances Wysocki (2004), following Andrew Feenberg (1991), advocated. And, as we discuss in the conclusion to this section, we understand our disruptive composition here as a form of critical making, as described by Matt Ratto (2011) and Garnet Hertz (2016), that challenges the "[c]alls for invisible and transparent computing" critiqued by David M. Rieder (2017, p. 69).

Perhaps Carter (2016) asked the field to disrupt the status quo because that status quo is what is safe—it's what the field knows is reliable and in many communicators' wheelhouses. Accepting failure through tinkering with ideas and concepts that are less in the safe zone of composition and technical communication could be exactly what is needed to break the mold. As Steven Hammer and Aimée Knight (2015) suggested, "By inviting some malfunction into our teaching and learning practices, we craft a different relationship to both our systems and our technologies." It's not about trying so hard to create something entirely new out of nothing. Instead, it's taking the tools that we already have available to us and repurposing them for something different—disrupting their usual routine into something new.

Along with other benefits of using the littleBits products in the pedagogical sense, as we discussed in the play section, inviting this kind of disruption, or malfunction, into the learning process also enabled stronger collaboration between group members. Since both the littleBits and the disrupting processes were foreign to our group members, it helped to encourage more creativity and outside-the-box thinking which, in turn, offered more voices to be heard and more ideas to be considered.

The Assignment

Our assignments for the littleBits projects were relatively straightforward—a promotional video to teachers and students explaining littleBits and a series of instructional deliverables (some of which we discuss in the redesign section)—until the last task: "an instructional video about a machine that purposefully fails." Using Carter's (2016) CCCC address as inspiration, we set out to create a machine that purposefully failed with littleBits: an over-the-top automated study station.

Brainstorming for the Study Station

After reading the assignment description and deliberating who would be tasked with what responsibilities, we asked ourselves: Where do we begin? In fact, we asked this question so often, we too were like a failing machine. What should we create? Why should we create it in such a way? And importantly: What do we know how to build?

We began with what we knew. Since this was our final project, we started to brainstorm all of the inventions that we had already created with littleBits. Since we had built and played around with several different kinds of machines, we had a base knowledge of what could or could not be done. Although our knowledge was not necessarily extensive with all of the capabilities of littleBits, we had a solid grounding on several of the different kits that were available to us.

All five of us sat around the room throwing out ideas of what we could do. Almost every idea centered around something that we had already created. We had a difficult time trying to come up with something completely original that we hadn't built or seen built in the instruction sets provided with littleBits. We then realized that was exactly what disrupting was all about: taking something that you know how to do and turning it on its head. We could take what we knew how to do and change it to disrupt its normal function. We already built machines that could light up, run a fan, make sounds via an MP3 player, and throw pieces of paper via a mechanized arm.

On their own, each of these machines worked perfectly fine with a predetermined task and purpose. We began to think about how we could start to combine different parts of these working machines into one giant machine.

Failure and Progress

Once we decided that we wanted to try and combine different parts of the working machines we had originally created, it turned into a bigger learning process than we had ever anticipated. Each one of these machines had been created in isolation. The lights were a small machine that only required a few pieces attached—the same pieces that were needed to create the small fan or the MP3 player. We realized that all of these machines needed to be connected somehow, as littleBits was limited in terms of pieces that allowed for a power supply (with only 5 kits, we only had 5 power supply modules—one that connected to USB and 4 that connected to batteries). On several occasions, we would try to connect too many pieces to one power source and the piece that was furthest away from the battery wouldn't work or turn on. Similarly, some buttons that we anticipated turning on certain features would turn on/off other ones that weren't meant to be activated.

We began tinkering back and forth with what pieces could be paired with others, which ones would need to be activated and turned on at the same time, and in what order they would need to be placed in the circuit for the battery to still be able to reach all of them. We learned more during this process than we had anticipated or could have imagined, since before this, we were mostly following the instructions laid out before us in the littleBits instruction sets. This act and process of disruption allowed us to consistently fail when our pieces didn't work, or didn't work how we thought they should, as well as aiding us in learning more about building with littleBits. This required some of the more advanced members of our team to take the lead in connecting the pieces and making them work, while other team members helped with the ideas of what we could do, how to use the pieces, and what the final product would look like. The collaborative effort increased here as we ventured into building something that did not already exist in a littleBits instruction booklet or on their website.

Final Disruption

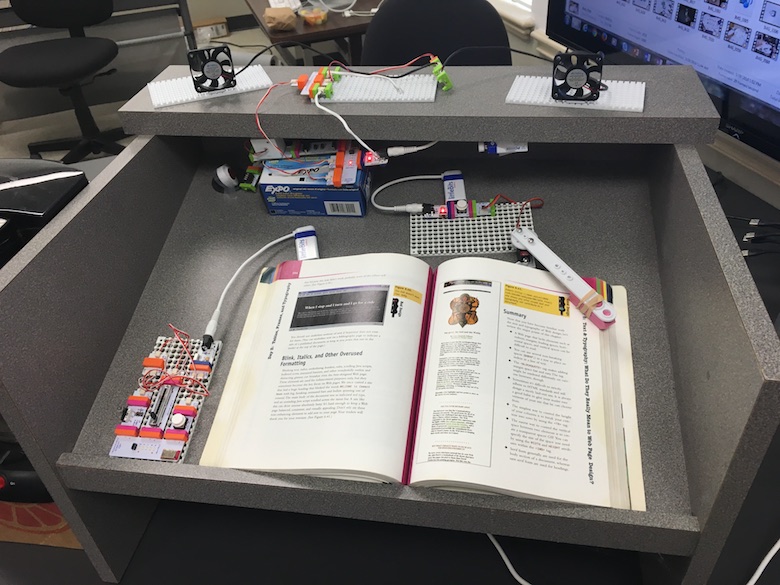

Our final disruption that purposefully failed was our over-the-top study station. Since the assignment description mentioned the fail videos of YouTuber Simone Giertz (2015a, 2015b, 2015c), we decided that one of us would be an actor to help sell the ridiculousness of our final product. Jack volunteered to act it out, and our final video was recorded in the English Department Media Lab. It was one thing to just take a picture of each part of the giant failing machine, or to take a video of everything laid out on a table. It was another thing to actually have a team member act in the video and speak about the scenario in which they were trying to use such a ridiculous machine. We felt that it added that necessary component of showing just how over-the-top the machine was and that, when it ultimately failed, there was almost no reason why somebody would want this to actually exist, or to create it.

(Note: This video uses the song "Swing Backward" by Alexey Anisimov [2016], used under a purchased Jamendo license.)

Before this purposeful failure, all of the previous failures were accidental, part of the learning process (which we discuss in the play section). It was only after developing a degree of familiarity that we were able to purposefully fail with a littleBits invention in a significant way. Over the course of nearly two weeks, we had developed considerable knowledge about littleBIts from our previous inventions. We knew how pieces worked together and in tandem with one another; we had developed a sense of how parts could be reassembled (both together and with other found objects) into new inventions (such as how we combined the fan and an MP3 player, or the throwing arm with an eraser attached to it to turn a book page).

We find our purposeful failure here—our disruption of an automated study station—significant because our process "decanonizes the process of making" (Hammer & Knight, 2015). Rather than conventional composing practices, which can be rote and unsurprising, our composing practice, drawing on available commonplaces like littleBits and other three-dimensional objects, was a practice of discovery. We spent considerable time over the two weeks of this course discovering what we could do with littleBits. We suggest that such purposeful failures are akin to the composing aesthetic promoted by Geoffrey Sirc (2002). Describing Duchamp's art, Sirc advocated for "failures that really aren't… writing done by anyone-whoever: useless, failed, nothing-writing by some nobody that turns out to be really something" (p. 35). Thus, Sirc argued for a mode of composition that delights, surprises, and even fails rather than the conventional academic essay.

Indeed, we see our purposefully failing study station, and the video we created that accompanies it, as an implicit aesthetic critique of academia as usual and of technological cultures that value automation and efficiency. In the opening scene of the video, Jack complained about the material conditions of being a graduate student and studying: The room is too hot with poor lighting, the materiality of books don't cooperate, spaces become materially cluttered. He "wish[ed] there was some easier way to do this" and wondered "could littleBits help?" Our group then set out to design an automated study station to make studying easier: "Why not make that all automated with littleBits, right?" But as our video showed, such an automation fails, in part because of the ridiculousness of automating several simultaneous tasks: brewing coffee, playing music, running a fan, and turning the pages of a book. While partially successful (the fan does blow, and the coffee does start brewing), the machine fails at the most mundane task of all: turning the page of a textbook. In doing so, our disruption disrupts the cultural drive for automation and efficiency. As Ian Bogost (2015) has written about the Internet of things and ubiquitous computing, "the Internet of Things mostly allows us to do what we already do, but with slightly greater efficiency. Or, if we’re really honest with ourselves, with the same efficiency, but presented in a different way: via a computational mediator." While our use of littleBits wasn't computational (though we could have connected the invention to a wireless network and added more automation, controlling the device through a cell phone), it does show that such drives for automation and efficiency are perhaps not really that much more efficient, just mediated differently. Further, we might suggest that our automated study station also critiques quick and easy solutions to the material conditions of being graduate students. Jack's wish for "some easier way to do this" in the opening scene of the video set up the solution to fail to make it easier.

While the automation didn't make Jack's studying easier, the process of composing collaboratively certainly made his graduate school work more enjoyable. Embedded in this process was play and experimentation for our group. The goal of failing and disrupting aided our creative thinking in imagining what was possible. It prompted the sorts of problem-solving activities that we could approach collaboratively, perhaps disrupting graduate education's most tried (and tired) habitus: the lone scholar working independently on his or her individual projects.

Packing Up: Disruption, Collaborative Craft, and Critical Making

Although this was just a small project for an intensive two-week graduate course, littleBits enabled us to not only determine what disrupting the composition process might look like, but also determine how and why disrupting in our field is important and how it can make an impact moving forward. The concept of disrupting enabled a unique perspective on composing and creating new ideas, materials, and processes that made both the individual communicator and group work outside the comfort of well-known and proven techniques. This worked to the benefit of the group and the final outcome, as it allowed for some innovating ideas that we might not have considered otherwise. The "democratization of electronics" (Bdeir, 2009, p. 397) made possible by mass-produced modular electronics like littleBits allows for the collaborative crafting that Wysocki (2004) touted as possible in new media composition: one in which composers can "see a possible self" in the objects they create (p. 21). In this case, the selves created by composing with littleBits were collaborative selves, ones that challenge the traditional subject position of the isolated scholar working individually on her or projects.

Further, we understand our failed automated study station as an example of what Ratto (2011) called critical making, a practice of “[using] material forms of engagement with technologies to supplement and extend critical reflection and, in doing so, to reconnect our lived experiences with technologies to social and conceptual critique” (p. 253). Ratto's goal in theorizing critical making was to merge the practices of social criticism—historically a conceptual and linguistic practice—and the practices of physically making things. As Ratto and Stephen Hockema (2009) explained, "critical making is an elision of two typically disconnected modes of engagement in the world—'critical thinking,' often considered as abstract, explicit, linguistically based, internal and cognitively individualistic; and 'making,' typically understood as material, tacit, embodied, external and community-oriented" (p. 52). For Ratto, following Seymour Papert's (1993) constructionism, the ultimate goal of critical making isn't a final product, but rather "a practice-based engagement with pragmatic and theoretical issues" (Ratto, 2011, p. 253). While Ratto emphasized practice and process, design and media arts scholar Hertz (2016) has revised his theory to attend to final products as well. Hertz argued that Ratto's concept of critical making is "useful in reintroducing a sense of criticality back into post-2010 maker culture." Whereas maker cultures can be de-politicized, techno-utopian, or overly reliant on ideals of American self-reliance, Hertz saw critical making as an opportunity to intervene in maker mentalities. By marrying criticality with making, Hertz proposed that we can build material speculations, or "built and functional devices" that "materially articulate particular stances and ideas" and that "can enable individuals to reflect on the personal and social impact of new technologies."

By engaging in a maker rhetoric project that purposefully failed and called attention to values of efficiency and automation that might be challenged and questioned, we see our practices as the sort of critical making advocated by Ratto (2011) and Hertz (2016). Our automated study station calls attention to and critiques the values of many physical computing technologies that Bogost (2015) critiqued: automation and efficiency. In Suasive Iterations, Rieder (2017) argued that advocates of physical computing have relied on an ideal of "calm, invisible technologies" that blend into our environments and go unnoticed (p. 69). In response to this ideal, which he understood as anti-rhetorical, Rieder argued for experimental inventions that bring attention to the material objects we invent with. By creating a machine that purposefully fails at automation, our new media project questions the value of such calm, invisible technologies that supposedly add efficiency to our lives.