- Home Page

- Story File (Blorb, 1.1MB)

- Source Code (link)

- Complete Text (TXT file)

- C&W Keynote Text (PDF, 250KB)

- Partial Map (PNG, 2.45MB)

- Kolam Rhetoric (JPG, 240KB)

- Play In-Browser (link)

- Notes (link)

perimortem [in (theoretical) rigor]

© 2024 by Vyshali Manivannan

Video Walkthrough

Transcript

In composing perimortem [in (theoretical) rigor], It was important to me to craft an experience that would challenge players, at times to the point of frustration, but wouldn't overwhelm them into disengaging. This meant designing game mechanics that are intuitive, easy to learn, and that accommodate experimentation; providing players with a sense of autonomy around morally grey choices; implementing a progression system that rewards player persistence with points, items, and the text itself; and ensuring that the game is accessible to players of all skill levels. To that end, while the game is meant to be played through experimentation with language, the text contains explanatory and assistive features that allow the player to adjust difficulty as needed.

All players—especially first-time players—would benefit from reading the prefatory material in the game. I tried to include specific content notes where they occur, especially in the Minefield area, but players should type "warnings" for a list of general content notes. Typing "about" offers a spoiler-free teaser for the game, with a footnoted Inventio reflection as well. Typing "how to play" generates brief instructions and a nonexhaustive list of the primary verbs you'll use during play. These instructions tell us that entering "note plus number" after encountering a bracketed number in the text will pull up an Inventio-specific output, so now that we know this and have encountered footnote [1] under "About," we can type "note 1," which gives us this Inventio output.

And finally, players can access a hint menu by typing "help" or "hint." (Players using screen readers should press "S" to enable screen reader functionality in the hint menu, as it's treated by Inform as a separate feature—notice how the command line changes when we're on the menu screen.)

To try to preserve the delicate balance between the painful experience of frustration and the motivation to continue playing, I organized these hints into five sections based on player location and specific events or puzzles. Each list of hints begins subtly and becomes increasingly explicit every time a hint is accessed, so players can try to explore and solve puzzles on their own as much as possible.

To use the hint menu, choose a category by entering its corresponding number, then enter the number that corresponds to the location, event, or puzzle you need help with. Typing "h" will generate a sequence of hints about that subtopic. For example, entering "1," "1," and "h" takes us to a submenu with 13 general hints about playing the game. If we don’t want other general hints, typing "L" returns us to the top-level menu. Now, for hints specific to the Storage Closet—the first location in the game—we can type "2," then "1" for the only available question, "What am I supposed to do in the Storage Closet," and then "h" for the first clue, which implies that trying to leave the closet while the examiner is in the Autopsy Chamber will lead to a bad end. Continuing to type "H" in any of these topics will generate increasingly specific suggestions and solutions.

The "Possible Endings" category is slightly different from the others, as it provides hints about achieving different endings. As this is a demo, there are really only two endings, but there are a few different ways—differently narrativized—to obtain them. If we return to the top-level menu again and enter "5" for "Possible Endings," then "1," then "h," we first receive a general description of the hint category; typing "h" again explains how to achieve one possible ending.

Instructions on playing and the hint menu can be accessed at any time during gameplay by typing "how to play" or "help," respectively.

As a kid, I consumed the accompanying booklets and official walkthroughs because I enjoyed reading them. Since this "out-of-world" content was usually written by the composer in an informal, humorous style, I thought of it as paratextual material that extended my knowledge of the game world, shed light on the composer's intentions, and was pleasurable to read. While the point of perimortem is struggle and failure, I encourage players to read the hints as well, as part of a "complete" game experience.

I have tried to honor the fact that using hints, dying intentionally, and performing actions that are inappropriate, forbidden, or out-of-character are part of the cultural history of games. Drawing on the illicit delight I still get from mischievous play, I modified the parser's compendium of commands and responses to realistically or humorously respond to such actions, some examples of this including "eat bag," "shit," and "fuck self." Additionally, sensory commands produce room-specific output that range from literary description to Infocom humor: For instance, in the Storage Cabinet, "listen" further describes the setting, while "taste cabinet" generates a humorous admonition.

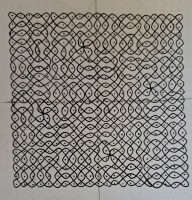

Finally, the left sidebar links to the following: the index; the "Play in Browser" website; the story file (if you'd prefer to play with an interpreter); the source code; the transcript of the keynote I delivered at the 2024 Computers and Writing conference; a partial map of the Minefield region; and the hand-drawn 21x21 kolam that serves as the geometric notation for the full game.

For the sake of players who wish to attempt things on their own, I won't reveal any more of the game here. As the game invites you to do, explore and experiment—the design will come, and thanks in advance for playing!