Offshore with Cynthia Haynes

Charlotte Lucke

Diane Beltran

Cynthia Haynes is a Professor of English at Clemson University, in Clemson, South Carolina. Long-time video game player, poet, and part-time Norwegian, she is the recipient of the 2017 Rhetoric Society of America Book Award for her work The Homesick Phone Book: Addressing Rhetorics in the Age of Perpetual Conflict (2016). Dr. Haynes's ideas about writing offshore have their roots in teaching and writing in digital environments, where she was at the forefront. Our interview asks about her thoughts about rhetorics, teaching, and writing. We asked about the theoretical foundations that inform and influence Dr. Haynes's teaching practices, and her understanding of the functions of past, present, and future rhetorics. We bring into focus the connectedness of her ideas to current situations, in and outside the academy.

Cynthia Haynes is a Professor of English at Clemson University, in Clemson, South Carolina. Long-time video game player, poet, and part-time Norwegian, she is the recipient of the 2017 Rhetoric Society of America Book Award for her work The Homesick Phone Book: Addressing Rhetorics in the Age of Perpetual Conflict (2016). Dr. Haynes's ideas about writing offshore have their roots in teaching and writing in digital environments, where she was at the forefront. Our interview asks about her thoughts about rhetorics, teaching, and writing. We asked about the theoretical foundations that inform and influence Dr. Haynes's teaching practices, and her understanding of the functions of past, present, and future rhetorics. We bring into focus the connectedness of her ideas to current situations, in and outside the academy.

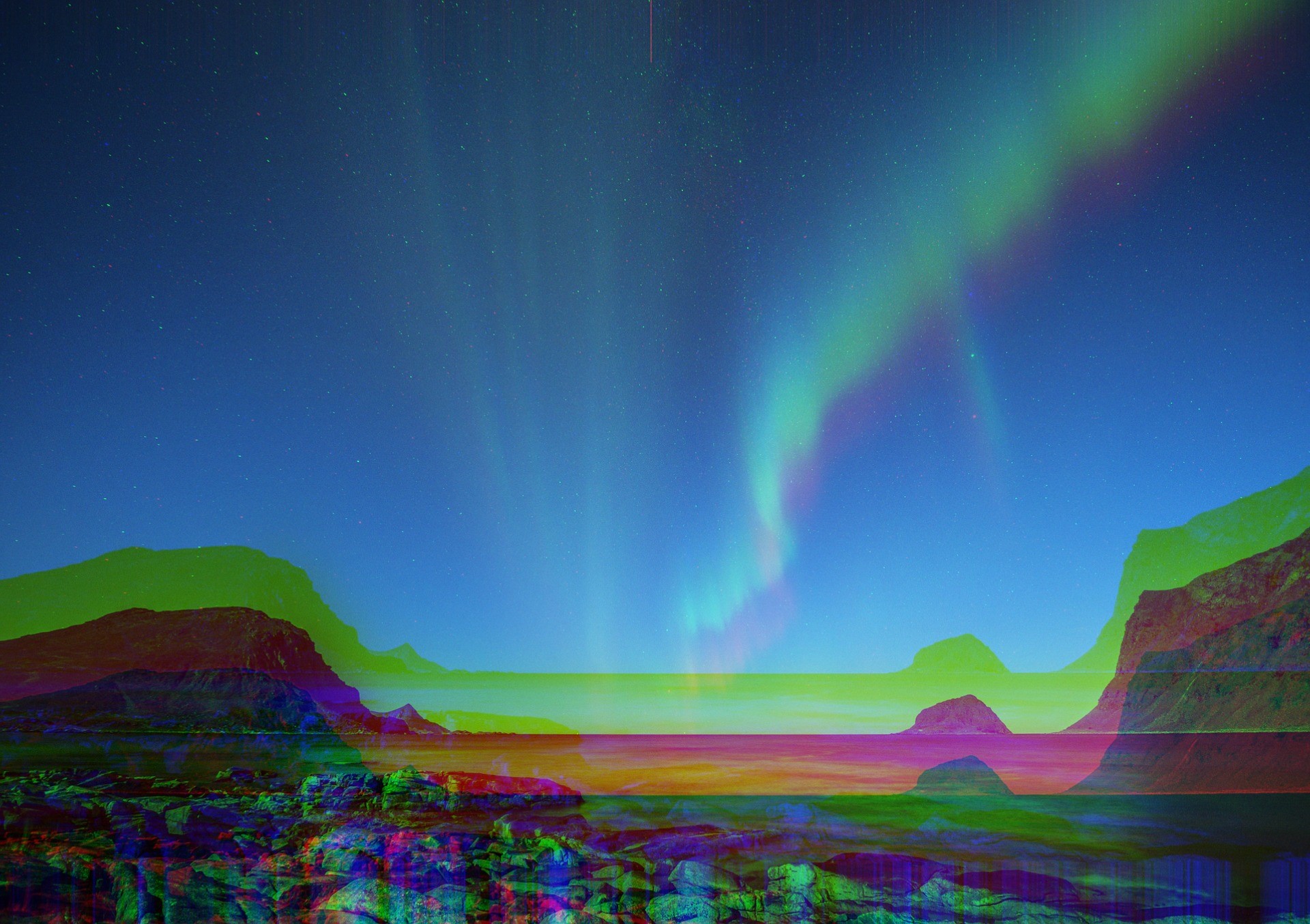

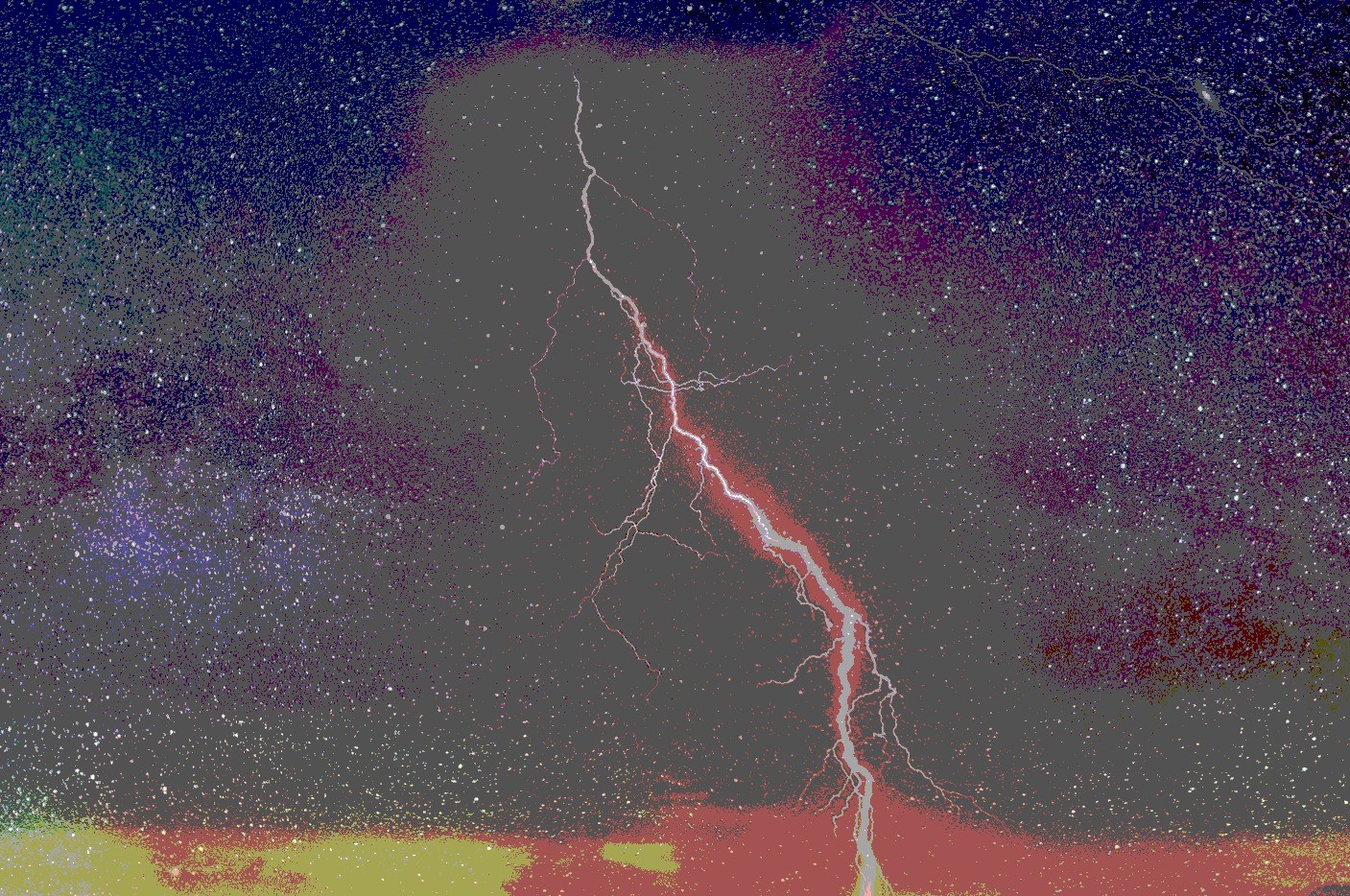

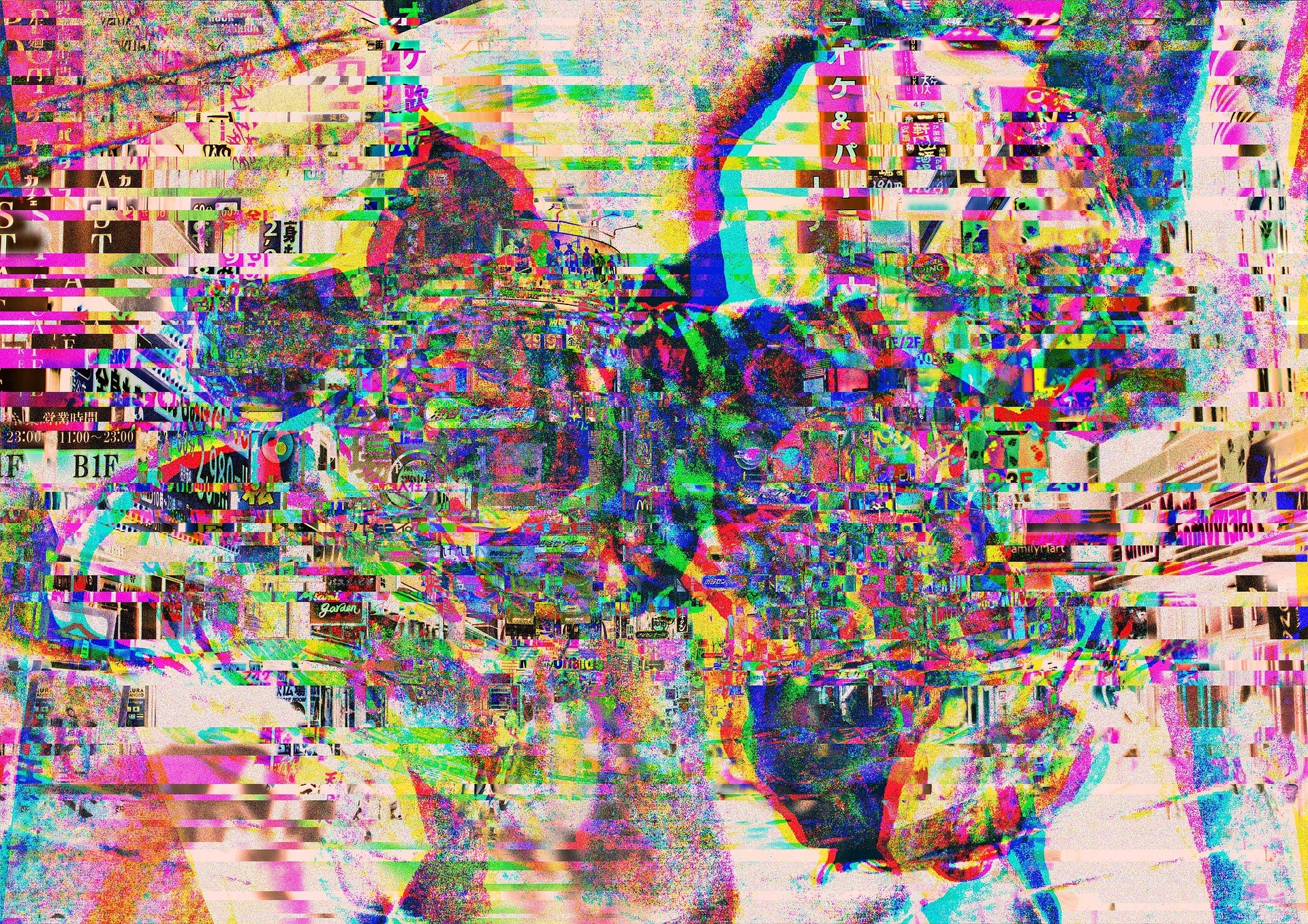

The following webtext employs two major themes which represent the theoretical principles behind much of Dr. Haynes's views on rhetoric, writing, and the teaching of both: the slash and the glitch. Additionally, the organizational structure also takes inspiration from Haynes's concept of the riff and the Nietzschean concept of backward inference, which he describes as a movement "from the work to the maker, from the deed to the doer, from the ideal to those who need it, from every way of thinking and valuing to the commanding need behind it" (Nietzsche, 2005, p. 272). In this, we ask viewers to dwell in the work of the makers, drawing and commanding their need in response to Dr. Haynes's reflections on rhetoric, pedagogy, and her past and future work.

The following webtext employs two major themes which represent the theoretical principles behind much of Dr. Haynes's views on rhetoric, writing, and the teaching of both: the slash and the glitch. Additionally, the organizational structure also takes inspiration from Haynes's concept of the riff and the Nietzschean concept of backward inference, which he describes as a movement "from the work to the maker, from the deed to the doer, from the ideal to those who need it, from every way of thinking and valuing to the commanding need behind it" (Nietzsche, 2005, p. 272). In this, we ask viewers to dwell in the work of the makers, drawing and commanding their need in response to Dr. Haynes's reflections on rhetoric, pedagogy, and her past and future work.

The slash is an attempt to conjoin similar or even disparate terms; the slash in relation to technology, for example, signifies both the merger and division between computers and writing. The slash also signifies the agonistic. Extended, the slash becomes the separator, the cleaver, and the dagger; from there, the slash takes on multiple meanings, including a Heraclitean lightning bolt as a flash of truth, as lightning rod and a grounding for lightning, and as a divining rod in search of water.

The slash is an attempt to conjoin similar or even disparate terms; the slash in relation to technology, for example, signifies both the merger and division between computers and writing. The slash also signifies the agonistic. Extended, the slash becomes the separator, the cleaver, and the dagger; from there, the slash takes on multiple meanings, including a Heraclitean lightning bolt as a flash of truth, as lightning rod and a grounding for lightning, and as a divining rod in search of water.

The glitch, or the fluke, is the moment when something goes wrong, whether it be language, design, or technology. It offers an opening or opportunity, a moment of realization or epiphany. Rhetorics like the glitch in our current age calls for a different way of understanding violence, scapegoating, and the uncertainty of the world.

The glitch, or the fluke, is the moment when something goes wrong, whether it be language, design, or technology. It offers an opening or opportunity, a moment of realization or epiphany. Rhetorics like the glitch in our current age calls for a different way of understanding violence, scapegoating, and the uncertainty of the world.

How to Enter (the interview)

The interview clips apply the notion of "writing offshore" (Haynes, 2016, p. 60) by employing nontraditional methods of argumentation and delivery. As such, you will notice there are no specified points of entry, no labels or explanations: just glitched images and slashes.

The interview clips apply the notion of "writing offshore" (Haynes, 2016, p. 60) by employing nontraditional methods of argumentation and delivery. As such, you will notice there are no specified points of entry, no labels or explanations: just glitched images and slashes.

Readers may select where in the chain of slashes and images they wish to enter, making real Dr. Haynes's (2016) notion that "rhetoric as refuge re-articulates the paths of the poets and illuminates their abstract trajectories. Displacing argument is rhetoric's supreme task; disinventing logos is rhetoric's sacred duty" (p. 99).

Clicking on a image will launch a video of Dr. Haynes speaking about rhetoric & composition, pedagogy, major ideas from her 2016 The Homesick Phonebook, and what she thinks the future of rhetoric-slash-composition is.

*Access a compiled transcript of the videos, including hyperlinked references.

References

Haynes, Cynthia. (2016). The homesick phone book: Addressing rhetorics in the age of perpetual conflict. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. (2005). Nietzsche contra Wagner: From the files of a psychologist (Judith Norman, Trans.). In Aaron Ridley & Judith Norman (Eds.), Nietzsche: The anti-Christ, ecce homo, twilight of the idols, and other writings (pp 263–282). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

About the Interviewers

Charlotte Lucke is a PhD Student at Clemson University's Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design Program. Her research interests include rhetorics, trauma studies, feminism, and theories of violence. Her current work focuses on these areas as they relate to domestic violence.

Diane Quaglia Beltran is also a PhD Student at Clemson University's RCID program. Her research interests are rhetorics of memory and forgetting in re-built and abandoned spaces.

Acknowledgements

Nathan Riggs, Visiting Assistant Professor of Technical and Professional Writing at Miami University's Hamilton Campus, assisted with the development of this webtext.