Timeline

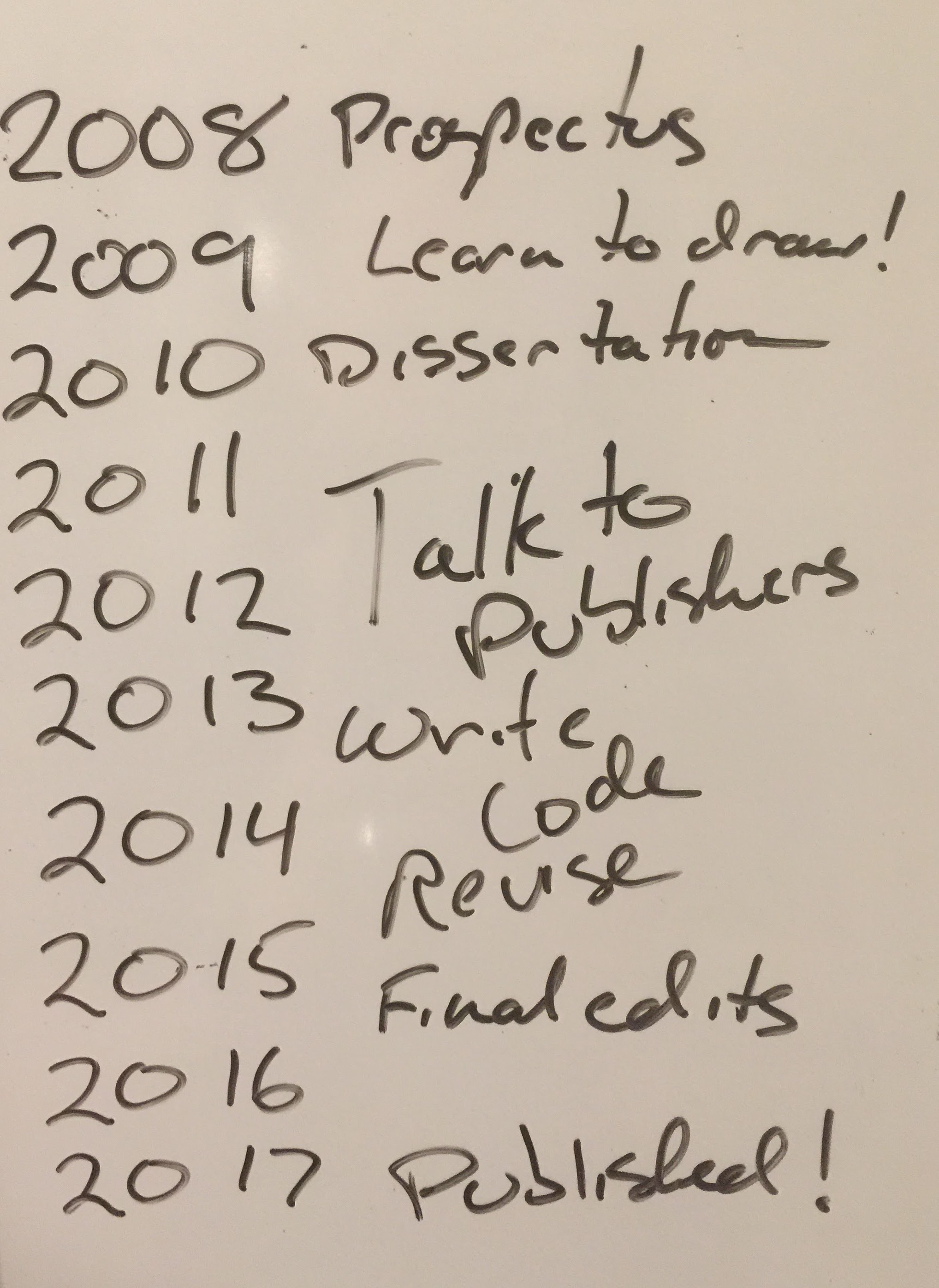

A photograph of a whiteboard with the various dates and tasks associated with Rhizcomics written on it.

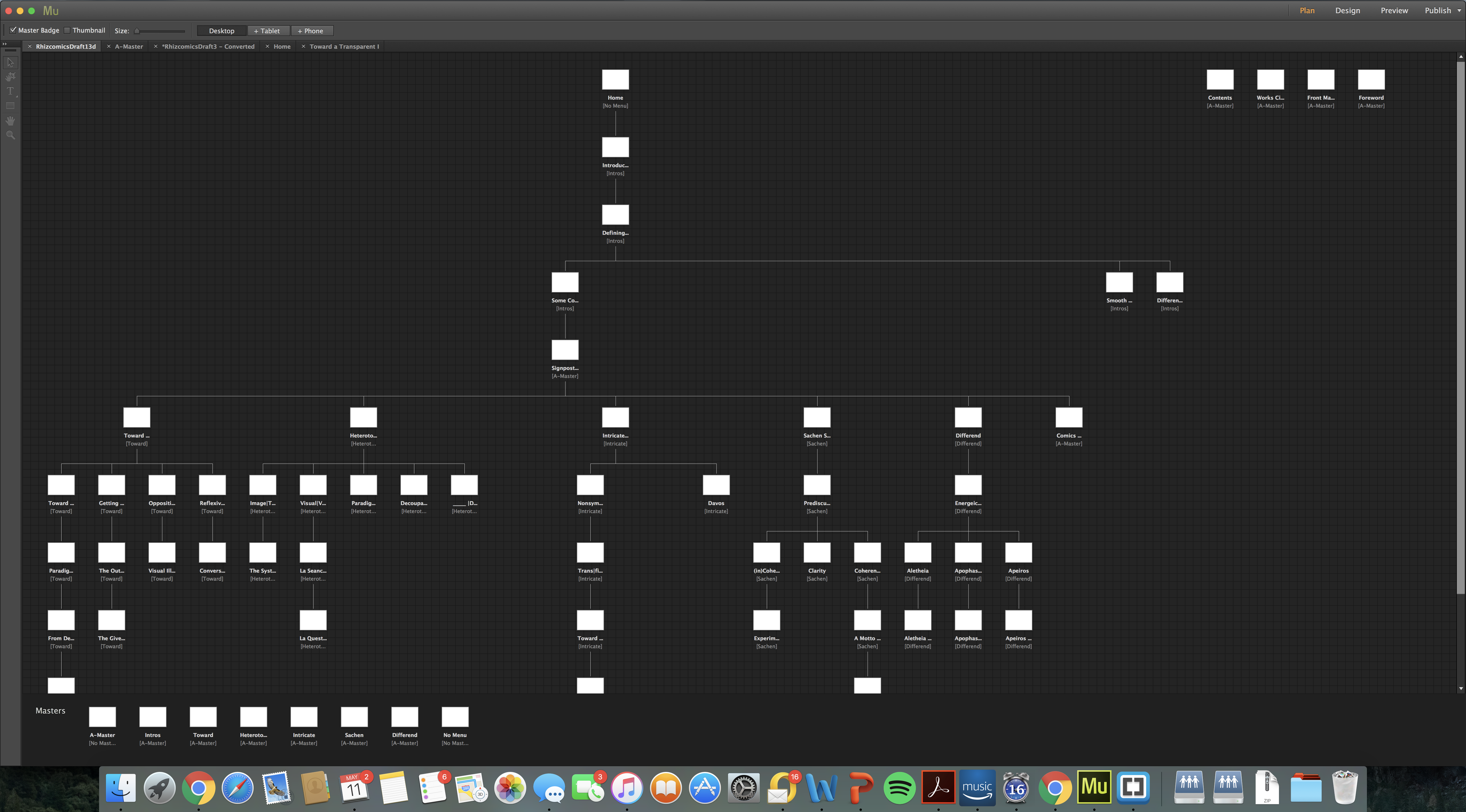

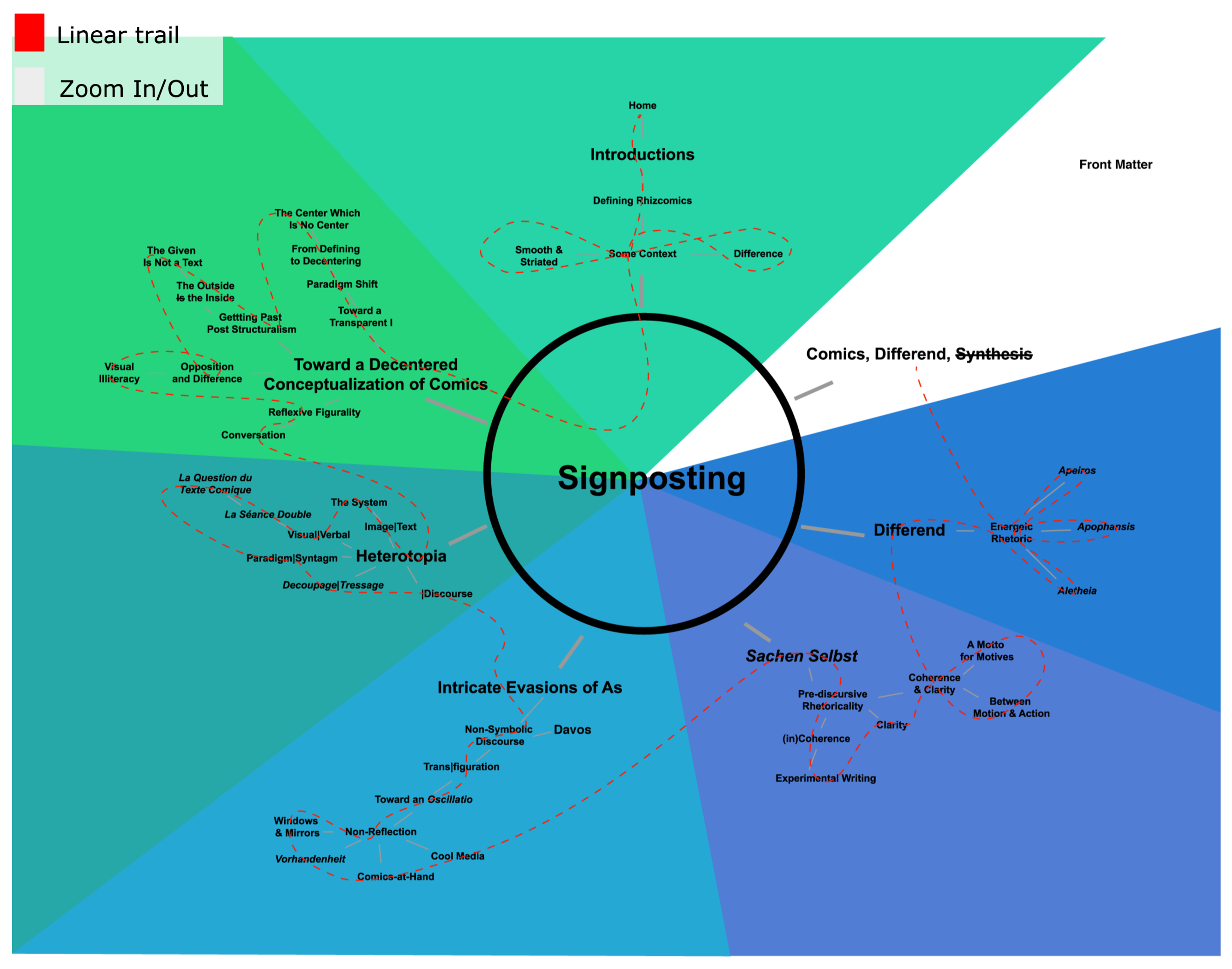

Across the next few sections, I've created a detailed timeline of the process of creating Rhizcomics. The timeline is divided into seven sections:

- pedagogy (2008-2014)

- moving from dissertation to monograph (2009-2014)

- preparation (2013-2017)

- composing and revising (2013-2014)

- converting to a website (early 2015)

- working with a press (mid to late 2015)

- final edits (2015-2017)

Many of these sections have subsections that can be explored by moving horizontally on the page.

In creating the timeline I've erred on the side of offering too much detail rather than too little. That level of detail will be important for some readers, but many can skim through the section titles or even move on to the practices that came out of this process.

Looking at the timeline from this view, it can seem daunting: almost a decade between the initial idea and publication! Some of this is certainly due to the time constraints inherent in digital publishing, but there were other factors that slowed me down just as much. From 2010-2012 I was in a post-doc and got very little done on the monograph at all. I focused instead on shorter pieces that would be likely to get published quickly and help me land a job. Much of the time was spent waiting on the press (and Michigan was by no means abnormally slow). Much of the time was spent thinking. A 10-year timeline from prospectus to monograph may be on the long side of normal for traditional scholarship, but it's certainly within the range of normal.

Preparation

Working with editors and tech specialists (July 2013–January 2017)

At University of Michigan Press, I worked with a variety of editors and other staff. Between my initial proposal and final publication I worked with three different editorial directors. This is just a side effect of a press changing directors: the initial director, an interim director, and the new director. This undoubtedly resulted in some longer than expected turn arounds and required me to be more proactive in contacting them. Each of the editors I worked with was skilled, professional, and helpful. They offered support for my ideas and guided me through the often mystifying process of proposals, contracts, reviewers, boards, and marketing.

These editors also helped me during conversations about permissions and copyrights. In terms of permissions, they took a very strong stance on fair use and offered me guidelines for whether the images I used from others would require permissions. In the end, I did not seek any permissions, but made certain that every image used was being analyzed carefully and was an integral part of my argument. This led to some images getting cut, but this worked out in my favor in that it made certain that none of my images were purely decorative—each had a purpose (requirement two).

They also offered me a variety of choices among the available Creative Commons licenses and helped me to understand their various advantages and disadvantages, allowing me to choose a license that would allow others to use my work without losing complete control of my work.

Early on in the project I began working with the director of publishing technology at University of Michigan. This was incredibly important at this stage because it set up what could and could not be done for the project. Fortunately, all of my ideas seemed achievable.

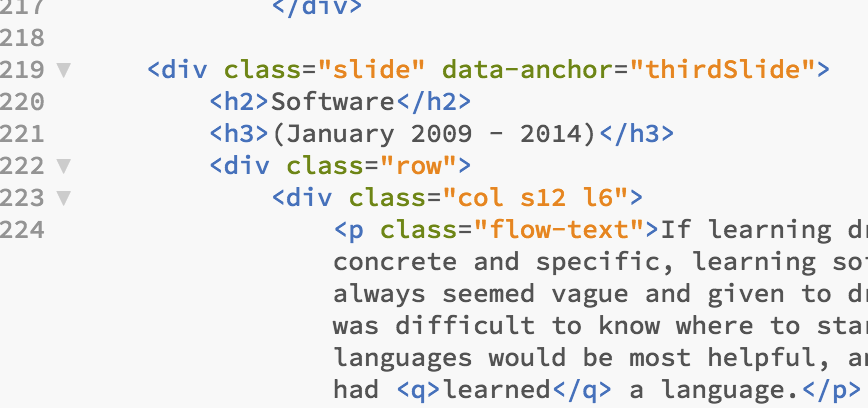

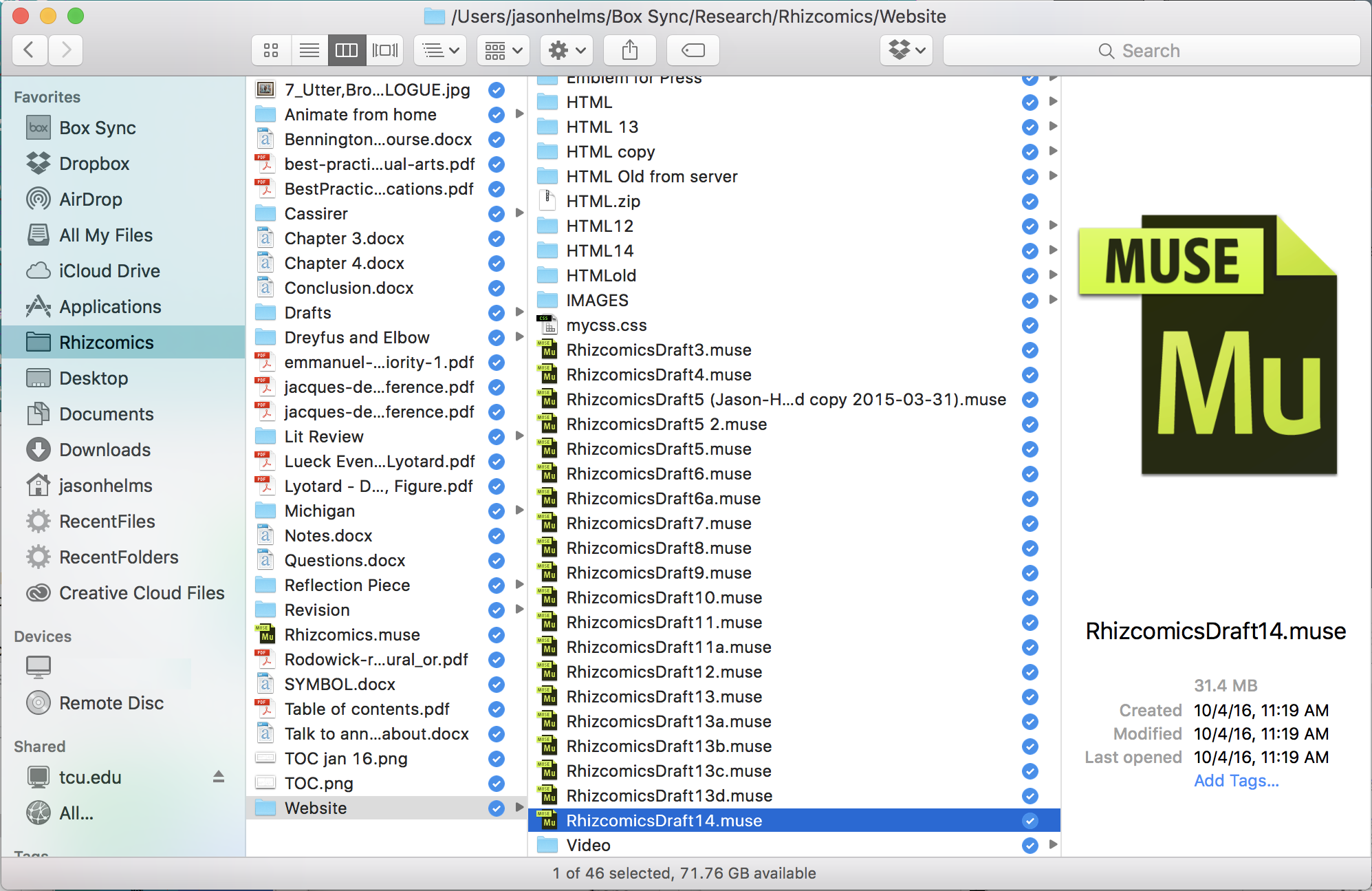

I would be responsible for creating the entire project and delivering the files to the press where they would place them on the server. This plan for a single site would get revised multiple times. The tech specialist and I continued to check in with each other as I crafted the site. University of Michigan offers some phenomenal guidelines for authors, including footers, style guides, and even code to be added to sites. He also worked closely with me during the revision process and while adding accessibility features.

Practices

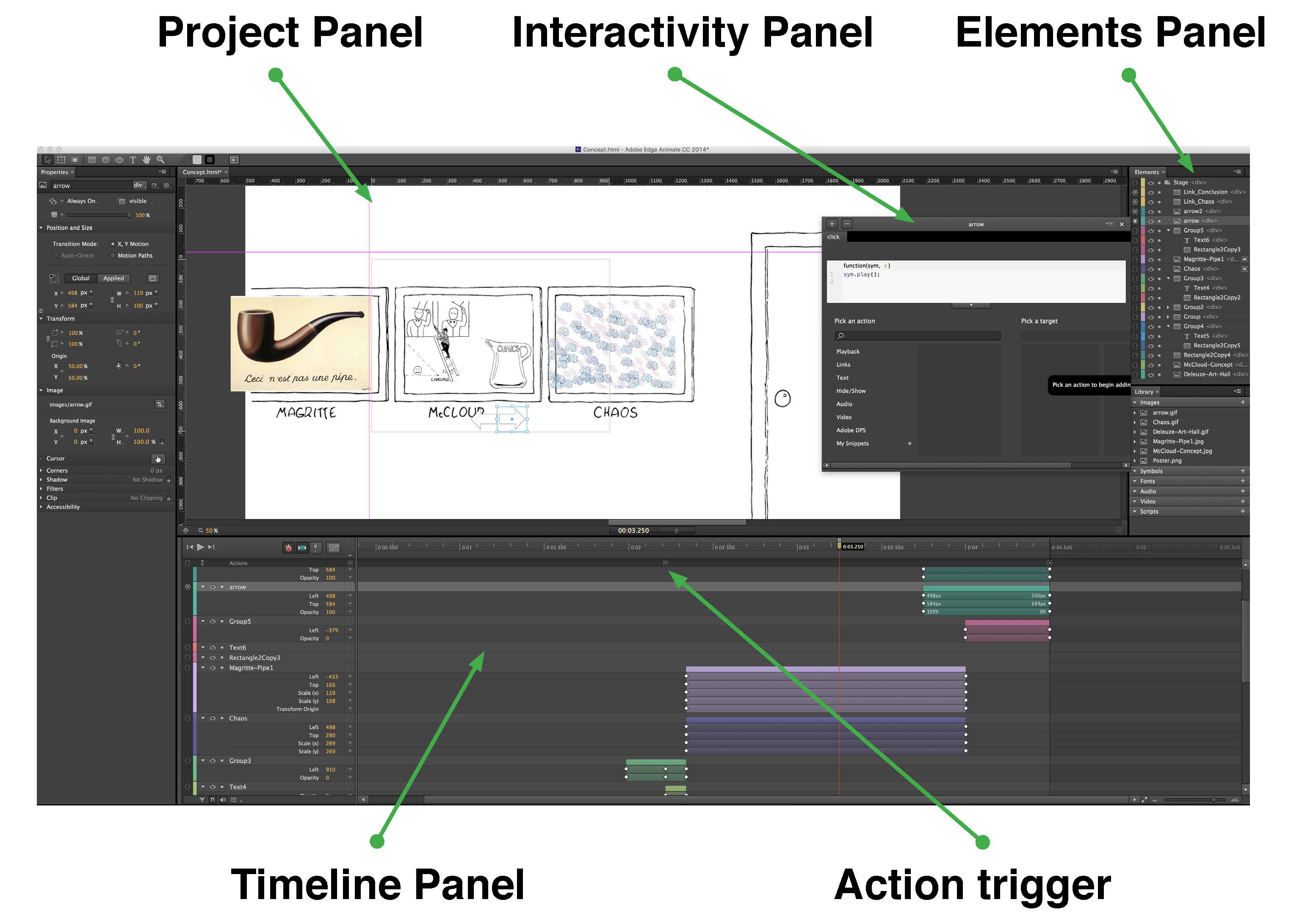

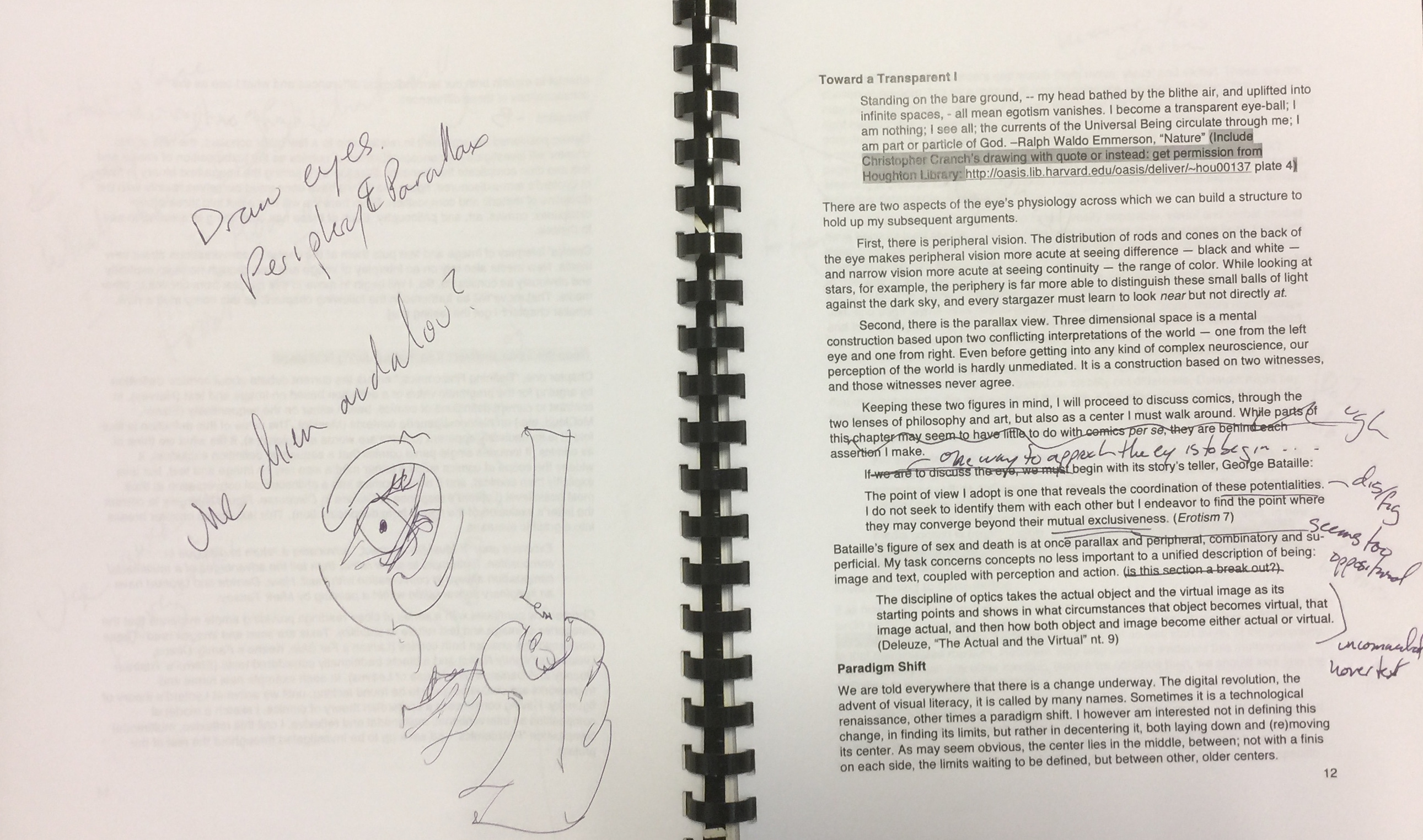

Designing, Scripting, Digitizing, Revising

This section is in place of a best practices section. I'm fairly uncomfortable with the phrase best practices. I like the practices but find the best presumptive. While the timeline above gets very specific, it often cannot dig deeply into specific practices that I employed throughout the process. Here I'll outline these practices, offering my reasons behind them as well as step-by-step descriptions of my own process. I'll also note places where my practices were far from best.

This section is divided into four major subsections:

Recommendations

After reflecting on the entire process and my practices, I've assembled a list of recommendations for scholars working in this area. The list below is by no means exhaustive, but the recommendations could likely be applied to all long-form multimodal scholarship. Each of the bullet points links to a relevant portion of the Timeline or Practices sections.

These recommendations are distinct from my own requirements listed in the rationale section and referenced throughout. In fact, my recommendation to "create your own constraints" is what created those requirements. The recommendations are a summary of my (best) practices.

Conclusion

At this point, it is too early to tell how digital monographs like Rhizcomics will shape academia. My goal in writing this webtext was to make my own methodology clear enough for future scholars to create similar work. I hope that the granularity of my recommendations facilitates such work. On the other hand, I fear that such granularity could be read as a how-to manual. I did not describe my methods in such detail so that others could imitate them, but so that they could avoid some of my mistakes and blaze new trails.

Perhaps the most important component of this webtext is the requirements I gave myself, repeated here:

- Form and content should be imbricated (Ball & Moeller, 2008)

- No visual intervention could be purely decorative (Elkins, 2003)

- The arguments should be shot through with the figural (Lyotard, 1971/2011)

- All analyses of visual examples should focus on their visual aspects (Elkins, 2003)

- New tropes and techniques should make the materiality apparent (Wysocki, 2004)

While these requirements can be applied in most digital scholarship, each scholar must create their own list based on their own research questions.

I'm excited by the work I see graduate students and newer scholars doing. I hope this webtext can encourage them in their work. I urge them to be bold and new, exploring new methods and making old media new.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the English Department at Texas Christian University for providing me with two research assistants during this project. Terry Peterman spent hours looking for previous scholarship on born-digital monographs. Unfortunately, there is still very little out there. Abby Long tirelessly moved my words from a Word document to this HTML file. I cannot thank them enough. My faculty mentor, Brad Lucas, gave me the intial idea for this project way back in 2013 before Rhizcomics had even found a publisher.

This webtext would not have been possible without my editors at the University of Michigan Press and the Sweetland Digital Rhetoric Collaborative. Rhizcomics was a challenging project and their flexibility and adaptability were essential. Thanks to Christopher Dreyer, Mary Francis, Anne Gere, Mary Hashman, Samuel Killian, Aaron McCullough, Jeremy Morse, Naomi Silver, Aaron Valdez, and others I may have forgotten.

I would also like to thank Anastasia Salter for introducing me to fullpage.js, Materialize, and this tutorial on full-page scrolling in JavaScript, all of which I used to create this page.

Finally, thank you to the readers who gave me feedback on this project at early stages: Joshua Hilst, April O'Brien, Amy Tuttle, and the reviewers at Kairos. I cannot thank you enough for your encouragement, honesty, and labor. I've never before had this much fun reading reviewer notes.

References

Anderson, Daniel. (2012). Watch the bubble. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 16(2). Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/16.2/inventio/anderson/

Ball, Cheryl, & Eyman, Douglas. (2015). Editorial workflows for multimedia–rich scholarship. The Journal of Electronic Publishing, 18(4). Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0018.406

Ball, Cheryl, & Moeller, Ryan. (2008). Converging the ASS[umptions] between U and ME; or how new media can bridge a scholarly/creative split in English studies. Computers and Composition Online. Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://www2.bgsu.edu/departments/english/cconline/convergence/index.html

Delagrange, Susan H. (2009). When revision is redesign: Key questions for digital scholarship. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 14(1). Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/14.1/inventio/delagrange/

Elkins, James. (2003). Visual studies: A skeptical introduction. New York, NY: Routledge.

Eyman, Doug, Ball, Cheryl E., Boggs, Jeremy, Booher, Amanda K., Burnside, Elkie, DeWitt, Scott Lloyd, Dockter, Jason, Dolmage, Jay, Gardner, Traci, Georgi, Sara, Hinderliter, Hal, Ivey, Susan, Keller, Michael, Kelley, Rachael, Kennedy, Sarah, Kennison, Rebecca, McClanahan, Pamela, Ries, Alex, Roberts, Kassi, Schlosser, Melanie, Stolley, Karl, Walter, John Paul, Williams, George H., Yergeau, M. Remi, & Zdenek, Sean. (2016). Access/ibility: Access and usability for digital publishing. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 20 (2). Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://technorhetoric.net/20.2/topoi/eyman-et-al/index.html

Haynes, Anthony. (2010). Writing successful academic books. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lanier, Jaron. (2010). You are not a gadget: A manifesto. 1st ed. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Lyotard, Jean-François. (2011). Discourse, figure (Anthony Hudek & Mary Lydon, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Mod, Craig. (2011). Post-artifact books and publishing. @craigmod. Retrieved March 26, 2018, from https://craigmod.com/journal/post_artifact/

Sousanis, Nick. (2015). Behind the scenes of a dissertation in comics form. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 9(4). Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/4/000234/000234.html.

Stiegler, Bernard. (2016/2015). Automatic society volume 1: The future of work (Daniel Ross, Trans.). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Stolley, Karl. (2016). The lo-fi manifesto. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 20(2). Retrieved March 26, 2018, from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/20.2/inventio/stolley/

Wysocki, Anne Frances. (2004). Opening new media to writing: Openings and justifications. In Anne Frances Wysocki, Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia L. Selfe, Geoffrey Sirc, Writing new media: Theory and applications for expanding the teaching of composition (pp. 1-42). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.