an introduction

This project, for me, illustrates the perfect example of a kairotic moment. The idea to do an expansive, feminist-focused review of Kairos webtexts had been on my radar for a while, but I had gotten sidetracked as I moved across the country and transitioned into a new department.

When I was assigned a new course, Feminist Rhetoric, I struggled to design content for the course that would cover everything from Aspasia and the Seneca Falls Convention to Ginsberg and Beyoncé.

Yet, the kairotic moment presented itself just as Kairos prepared to celebrate 20 years of influence in our field; I realized that my students and I could look back and re-envision a decade of Kairos webtexts through a feminist lens.

What follows is a retrospective of the scholarship published in Kairos from 2002–2012, but with the added intention of revealing the unseen feminisms at work in the journal.

My students and I identified implicit strains of feminism embedded in Kairos webtexts from that decade and then related them directly to a definition of feminist rhetoric that we built from our study of ancient and modern works.

Though the majority of the authors of the scholarship we analyzed did not—and may not—identify as feminist scholars, it is our hope that our analysis will create new bridges between those who may be united by some of the core values and characteristics we identify here.

As Kairos readers look back and celebrate two decades of work, we hope that this analysis reinvigorates and repositions not only the work in this journal but perhaps also the sometimes less-than-celebrated feminist label.

–Jen Almjeld, Assistant Professor of Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication at James Madison University

about us

We come from the Women and Gender Studies program; the Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication program; and the School of Communication at James Madison University.

Our review essay has been designed as a tool to highlight the feminist perspectives already at work within Kairos by identifying webtexts of particular interest to scholars seeking a feminist perspective.

We recognize that our voices do not represent the entirety of Kairos's academic discourse community. Some of us are rhetoric majors, as is our professor; however, many of us are in other fields, such as social work, women and gender studies, English, politics, justice, and communication studies.

Each of these fields represent a different set of scholars, methods, and conventions, so while many of us may be considered outsiders, we claim that outsider status and the way it rhetorically colors this webtext. We bring a fresh perspective to the scholarship in Kairos.

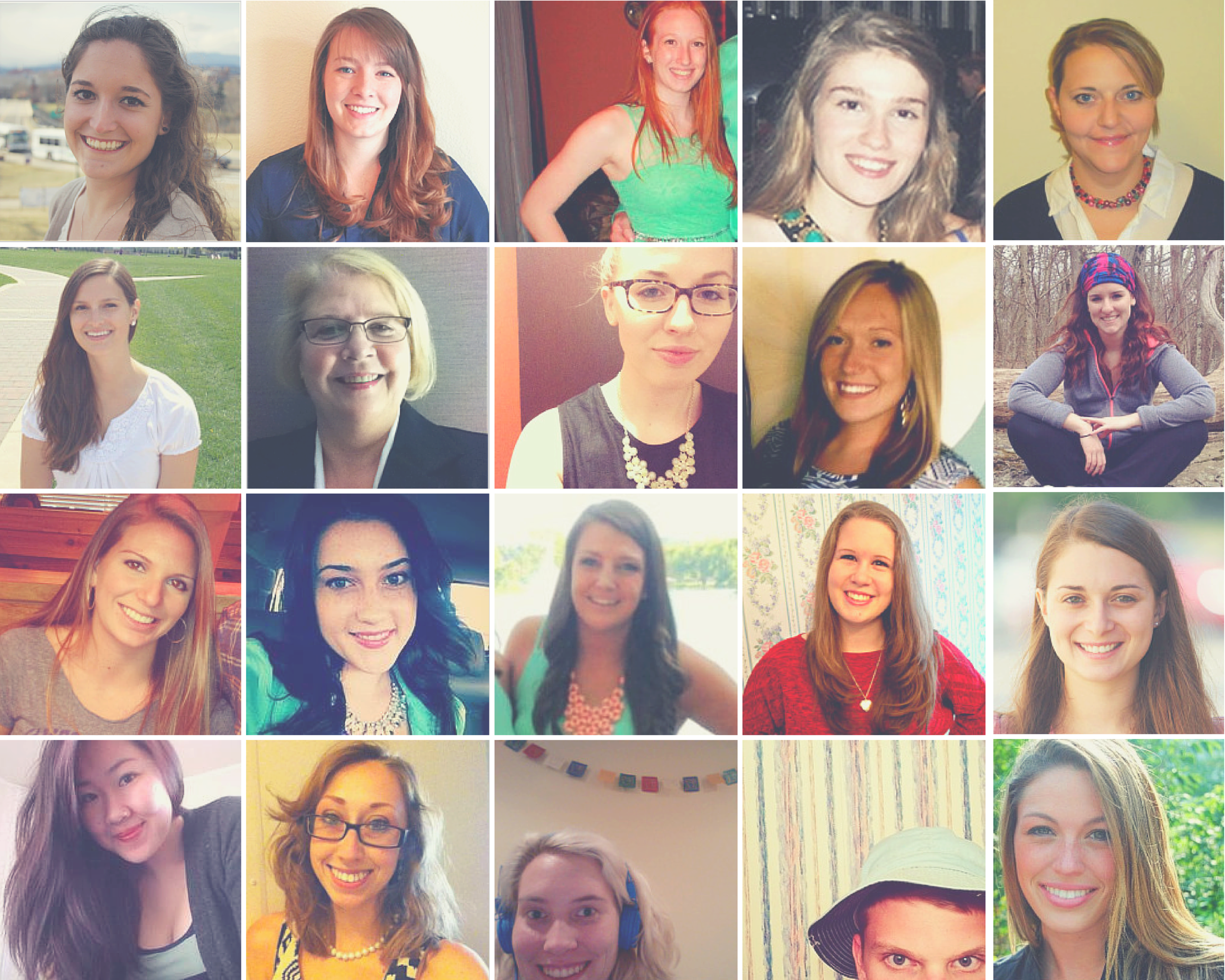

meet the class

our mission & philosophy

This review essay evaluates a decade of scholarship from a feminist perspective and, in so doing, encourages both journal contributors and readers to recognize hidden strains of feminism in webtexts appearing in this journal. While Kairos might not specifically identify as a feminist publication, there are many instances of latent feminism in works published here. On the other hand, many of the webtexts published in Kairos overtly engage feminist topics and concerns like gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. However, we hope our work might invite more authors to specifically situate their work as a feminist rhetoric and perhaps openly claim the term feminist for themselves. This reluctance of authors we see performing feminist scholarship to avoid labeling their work as such may be an intentional avoidance of the "f-word," a word with a history.

As an ideology, the feminist movement often avoids labels and categories. But we feel that there is a real power in using the "f-word" to define and re-define scholarship taking on the work of challenging norms and structures of power—in this case, often in the classroom and workplace—and in opening up new spaces for a variety of voices to be heard via a variety of modalities. Ultimately, many pieces of scholarship published in Kairos demonstrate various feminist rhetorical elements, and in doing so they challenge existing ideas that sometimes seek to constrain teaching and research in rhetoric, composition, and pedagogy.

Since we collectively produced this feminist review of Kairos, we thought that it was only fitting that the review itself adhere to the feminist rhetorical principles we identified in our class. An important first step in developing our commentary on Kairos's position within feminism involved coming up with a definition of feminist rhetoric that we could use as a point of reference. We agreed on seven terms that we felt were essential components of other standout feminist works to create our definition.

First, our review embodies the authors by providing bios that explain who we are and our own relationships to the project and to feminism. We not only include images and text about ourselves, but also include a video—despite its ametuerish production value—in hopes of connecting with readers as with more than words on a screen. Our review also gives a voice to our participants when we highlight the feminist strengths of Kairos and its publications. Similarly, we seek to validate various experiences by highlighting both hidden and obvious aspects of feminism impacting the journal. Like Kairos itself, our review essay is multimodal, incorporating both text and video in an attempt to increase its overall reach and accessibility. In terms of positionality, we are aware that we are not all experts in the field of computers and writing. In acknowledging this limitation, we position ourselves as curious outsiders interested in joining the larger conversation about the role of feminism in the discipline of rhetoric.

Having said that, we do not intend this to be your typical scholarly review essay. Seeking to explicitly challenge systems of power and the norms of traditional scholarship allows us to approach this review in a new way. Our review empowers different ways of being by celebrating a variety of rhetorical approaches, design choices, and narrative voices found in the journal. We hope this work inspires others to consider this publication as a space where feminist rhetorical principles are enacted, celebrated, and made explicit. We see our review as an example of how online scholarly journals like Kairos can promote accessibility for all ways of being and can be used as safe spaces for feminists to claim that title.

rhetorical roots

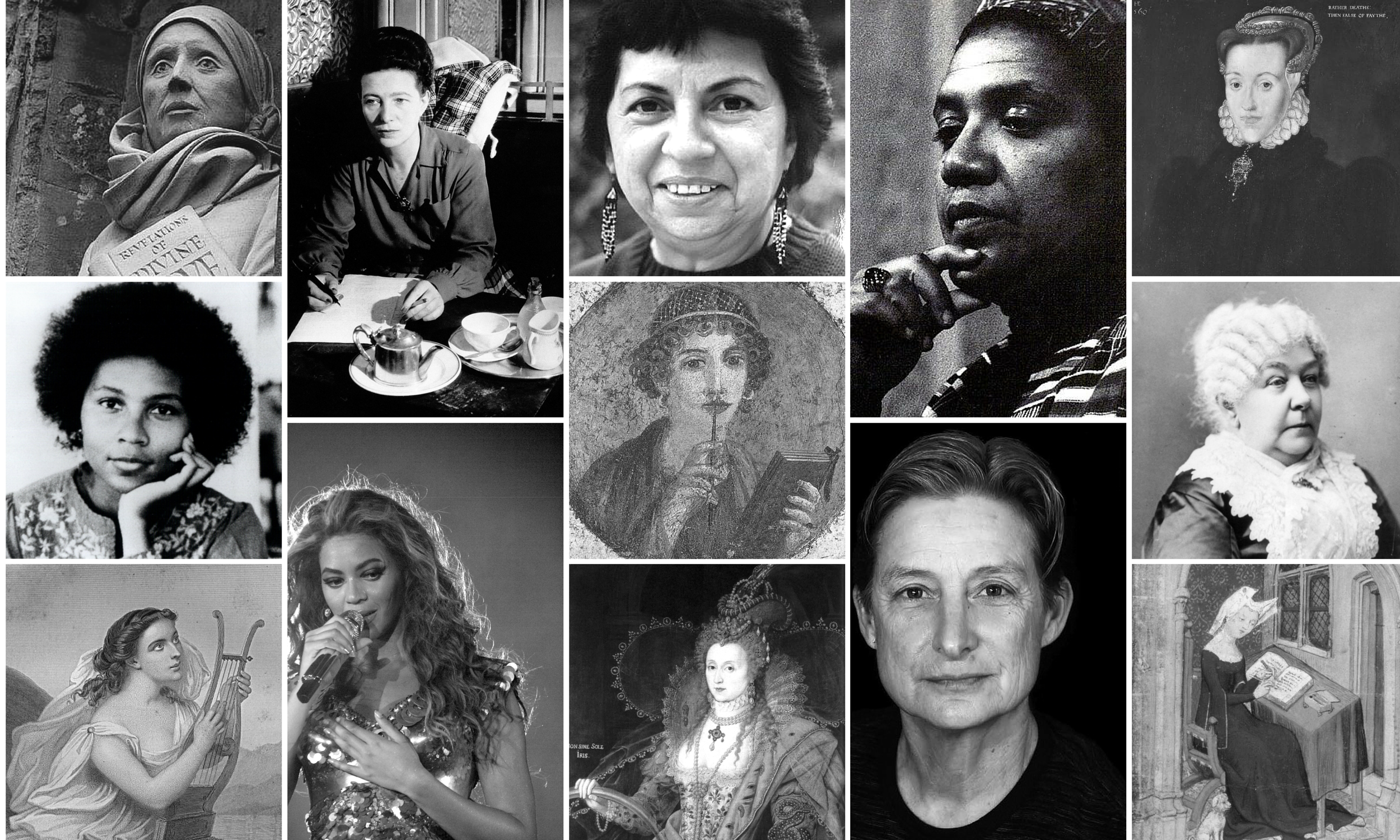

Our class began in the way that most feminist classes begin, by reading what we termed "the rockstars of feminist thought." We traversed decades of speeches, writing, and visual works by and about women. We began our study of feminist rhetorics with Cheryl Glenn's (1997) foundational text, Rhetoric Retold: Regendering the Tradition from Antiquity Through the Renaissance. This is where we began to re-map or re-claim the essential texts of female rhetors like Aspasia, Sappho, Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Margaret More Roper, Anne Askew, and Queen Elizabeth I. We also considered the work of contemporary feminist writers and scholars including bell hooks, Gloria Anzaldúa, Judith Butler, and Audre Lorde.

We examined ways these female intellectual figures had their work co-opted, ignored, or dismissed by authorities, and how the patriarchal practice of sexualizing female thinkers and public figures and devaluing their work continues today. Many of the works displayed a tendency to invoke power through their exploration of the relationship between body, spirit, and intellect; the growth of knowledge through religious and emotional expression; and an awareness of the author's own positionality and the challenges faced in giving voice to ideas others felt unfit for public spheres of rhetoric.

What emerged was a framework for defining historic and modern examples of feminist rhetorical expressions. As this list of characteristics emerged, we noted that many of these characteristics were also present in Kairos, perhaps most notably the use of multiple modes and the challenging of norms and systems of power—in this case in regards to academic publishing. What follows is certainly not an exhaustive list of feminist rhetorics, but is instead intended to ground readers in the terms we will use as we review Kairos issues and to understand how we came to choose these rhetorics as particular lenses through which to review Kairos. During our study of both canonized works of feminist rhetorics and what we consider covert feminist works in Kairos, we identified seven characteristics we feel mark a rhetoric as a feminist enterprise. We read feminist rhetorics as doing or being at least one of these.

feminist rhetorics are...

(select to expand)

embodied.

Margery Kempe, credited with writing the first autobiography in English, gained acclaim for publicly challenging notions of women's fitness to speak on spiritual matters. This important work was achieved by ignoring the distinction between personal experience and public and political rhetorics. Known for possessing the "gift of tears," Kempe is often dismissed as suffering hysteria rather than religious insight. But this linking of her corporal body with her intellect and spiritual awakening was exactly what gave her rhetoric power. The works of contemporary rhetorician bell hooks also embodied the scholar through grounding in her life experiences. "Sexism... is the practice of domination most people are socialized to accept before they ever experience other forms of oppression," according to hooks (Foss, Foss, & Griffin, 2006, p. 77). She established her experiences of familial patriarchy and institutional sexism in academia and addressed life events as not just relevant but crucial to feminist understandings, urging teachers in particular to allow students to discuss their unique perspectives. hooks writes memoirs alongside political texts and lets her experience cross over into her cultural theory, using her life as subject while diverting attention toward ideas and decentralizing her authorial self from her work's focus.

voiced.

In our reading of Joy Ritchie and Kate Ronald's (2001) Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric(s) , we encountered poet and activist Sappho, among others. Her words were neither humble nor apologetic in tone, but exuded confidence in voice and being. Sappho, perhaps best known for her sexual orientation, was an important rhetorical figure that gave voice to women's experience and feelings and also prowess in poetry, an arena formerly reserved only for men. Voice—whether one's own or afforded to others and often overlooked through a rhetorician's work—expresses linguistic identity and the performative power of language. In "Reflections from the Borderlands," rhetorician Gloria Anzaldúa explained, "I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white" (Foss, Foss, & Griffin, 2006, p. 105). She challenged dichotomies by exploring how interconnected body and intellect, language, and identity are to the individual. The blurring of this dichotomy allows for new self-identification from the participant. By encouraging individuals who are traditionally marginalized to locate their voice, they are no longer limited to the phallocentric language systems used as a means of oppression.

positioned.

Privileged, highly educated, and tremendously powerful, Queen Elizabeth I was a woman in a unique rhetorical position to say the least. She once said, "I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too" (Ritchie & Ronald, 2001, p. 48). To secure her position as monarch she was often forced to eschew her gendered existence, but she was always profoundly aware of the rhetorical context from which she spoke. Recognizing one's privilege and limitations is vital when taking on research. Our reading of Nancy L. Deutsch (2004) helped us understand how vital it is to recognize one's positionality when conducting research and the ways that position might impact participants. Deutsch's work explored her identity as a researcher and the ways in which that identity sometimes conflicted with her personal identity.

multimodal.

So many of the texts we read in our course began as other texts—as speeches like the one delivered at the Seneca Falls Convention, as popular songs like those of Beyoncé, as performance pieces and legal defenses. Anne Askew, for example, was a Protestant martyr put to death for her belief that women could speak in matters of faith and is perhaps most famously remembered for her rhetoric of silence. When she refused to answer the questions of her inquisitors, she shifted power and created a rhetorical appeal out of thin air. Like Askew, modern feminists utilize multiple rhetorical appeals to speak to various audiences. Feminist rhetoricians recognize the importance of accessibility to our works by making them available in vernacular and alternate modes. As well, they acknowledge multiple ways of learning, privileging multiplicity over the author-as-expert model.

validating.

Often the first step to challenging systems of power and oppression is to validate other ways of being and knowing. Julian of Norwich, venerated by the modern Lutheran and Anglican churches, validated the role of women in the church with her bold use of "I" in her writings—acknowledging her own right to speak. Her 16 "showings" or religious visions were the basis for her text, Revelations of Divine Love, but her radical contribution to the rhetorical canon was her feminizing of the trinity and insistence that the female was not at odds with faith. Like Julian of Norwich, Audre Lorde validated experience by showing women how they could use their difference to create stronger communities. "Because I am woman, because I am Black, because I am lesbian, because I am myself," Lorde wrote (Ritchie & Ronald, 2001, p. 301), and in so doing she claimed her unique voice. As a rhetor, Lorde constantly challenged what could be a public discourse for academia. By breaking conventions of her race and gender, she interrogated academia to recognize privilege while breaking the silence for individuals who could not speak.

challenging.

Perhaps most importantly, we see feminist texts as challenging systems of hegemonic power and normative practices. By disrupting these behaviors, new discourses surface and permeate the community of learning. Ancient female rhetorician Hortensia, voiced only through Plato in his Symposium, was important not only in her arguments for the valuing of women, but also in her ability to be heard in this male space. Diversity of being greatly relates to a diversity of intellectual thought, and therefore should always be the means to which systems of powers are challenged. Simone de Beauvoir challenged the very system of gender in her Second Sex when she reminded us that "one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman" (Ritchie & Ronald, 2001, p. 254). Similarly, Judith Butler challenged systems of power regulating gender performance with her writings, but did so in a manner that made feminist perspective and philosophy palatable for traditional academic readers.

empowering.

While not all rhetorical acts lead to change, many of the feminist rhetorics we studied sought to empower listeners and readers, even in the face of systems of power and oppression. Medieval author Christine de Pizan is often cited as the first woman to support herself by writing, and her work, The Book of the City of Ladies, celebrated the wisdom of women. And though suffragist and writer Elizabeth Cady Stanton did not live to see the 19th amendment passed in 1919, her impassioned writing about women's voting rights inspired future generations of suffragettes. No one piece of rhetoric alone could change systems of power that have marginalized and continue to marginalize, but together these texts—in all their forms—empower generations to act.

our definition

Feminist rhetorics are embodied in that they acknowledge the real person behind the scholar by honoring the personal and the political. This embodiment gives voice to participants and validates their experiences. It is also situated by recognizing positionality and potential bias of the reader. These rhetorics are more accessible to various ways of learning through a nontraditional multimodal presentation. Perhaps above all, feminist rhetorics challenge systems of power and norms set up through hegemonic principles by empowering all ways of being.

feminist rhetorics in Kairos

We spent the Spring 2014 semester immersed in feminist rhetorics and exploring a range of feminist topics spanning Aspasia in ancient Greece to multimodal composition scholars featured in Kairos. Individually each of us chose an issue of Kairos to examine that interested us personally. In our individual reviews, we focused on identifying instances, both hidden and intentional, of the seven key themes of feminist rhetorics we had agreed upon as a group. In the process, we began to see patterns of feminist strategies and values in current scholarship published in the journal. We then worked to meld these individual voices into a collective review. Our individual reviews gave us direction for our collaborative essay and provided us with a clearer idea of our underlying purpose. We placed ourselves into informal groups of writers, editors, videographers, statisticians, and designers.

Through our evaluation of Kairos we noticed feminist themes within the issues but also noticed that the word feminism was never mentioned in the webtexts we studied. As a Feminist Rhetoric class we found this omission curious, and we hope that this project encourages readers and scholars to imagine Kairos as a feminist space where issues of access, gender, socio-economic status, and other issues related to "the f-word" are frequently taken up. Additionally, we hope that our work might prompt some Kairos contributors to more overtly claim the title of feminist scholarship for their work.

our findings

We decided as a group to focus our coding efforts on webtexts featured in the primary sections of the journal: Features (which became Topoi in the 10th anniversary issue of 2006), CoverWeb (which also became part of Topoi in that issue, but then re-appeared as a separate section in the last issue we cover here, in Fall of 2013), Inventio, and Praxis. (All of these sections also happen to be the peer-reviewed sections of the journal during that decade.) The exclusion of the PraxisWiki webtexts, which can arguably be considered a featured section of the journal (particularly in more recent years, since it became peer reviewed, in 2014) happened for two reasons: the first is practical, because we felt we could not feasibly code any more than a decade's worth of webtexts from the peer-reviewed, featured sections of the journal in a 16-week semester. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, we wanted to devote our time to revealing some unexpected instances of feminism in the journal. The PraxisWiki—with its focus on "narratives, assignments, and short pedagogy pieces"—would no doubt have yielded tons of feminist work as it relates so closely to the classroom, but we wanted to concentrate our efforts on "re-mapping" those spaces not so obviously feminist. We also felt the webtexts in the featured sections more closely aligned in length and scope with more traditional scholarly webtexts—not surprising, given their peer-reviewed status—and so might offer interesting insights particularly in ways Kairos authors subvert traditional academic conventions.

As a group we read and coded 143 individual webtexts, authored by 277 writers and designers in 26 issues of Kairos. While coding the issues, we focused on identifying explicit and implicit instances of webtexts enacting the seven characteristics of our definition for feminist rhetorics.

This count of feminist markers began simply as a way for class members to mark one of the seven terms identified in our definition (embodied, voiced, positioned, multimodal, validating, challenging, and empowering) and help us see patterns across issues. We felt this sort of statistical approach might inform our work and might also allow another layer of accessibility to the work as statistics empower other ways of knowing and being in regards to scholarship. Below is a description of frequency in regards to each term.

10 years of authorship

Our focus on numbers continued with special attention to statistics related to authorship. We first coded authors' names for gender, any mentions of self-identified gender, self-identified credentials or degree, what institution the author represented, and whether or not the writer identified as a feminist. We chose to only report what was reported by the author in the webtext in order to best honor the author's choice of voice and electronic embodiment.

We noted interesting findings in three main areas: gender of the author (or lack of gender identification), author credentials, and whether or not any of the Kairos authors explicitly defined themselves as feminists.

To discover these aspects, we relied only on the webtexts and did not perform background research on any writers. When identifying gender, we made gender norm assumptions based on names and authors' photographs. We recognize that this binary gender assignment is problematic, but we also felt that identification of gender was important according to precedents in the field of feminist rhetoric (Glenn, 1997; Foss, Foss & Griffin, 1999; Ritchie & Ronald, 2001).

Highlighting author gender is also a tradition rooted in the computers and writing field. "It’s true that Kairos’ use of a modified version of APA style that shows authors’ first names was a conscious feminist choice," editor Cheryl Ball (2015) explained in an email. "Kairos wasn’t the first to do this—the practice was taken from the in-house style guide we used at Computers and Composition, when I was an assistant and associate editor there in the early 2000s." For Ball and her colleagues at Kairos, this practice was adopted "primarily to stop the obfuscation of gender in research roles, as names would be listed in the References list." Erasing or ignoring gender has impact not only for authors of the online journal, but also for ways we view the field as gendered—or not. "Our new focus … is to ensure that Reference lists aren’t dominated by male researchers. I’ve stated a few places publicly that if a submission doesn’t include any women on the references list, I’ll reject it out of hand. While that’s not totally true, it’s certainly a rule of thumb that I am trying to follow when working with authors to develop their research." These types of editorial decisions reinforce our reading of Kairos as a space open to and supportive of feminist ideals of inclusion and increased visibility for women.

We found that of the 277 authors listed in the webtexts we reviewed, 97% did identify their gender, and roughly half of those authors were females. Of the authors, more than half (63%) did not provide their academic or professional credentials in their webtexts. And lastly, of the 277 authors who have contributed to Kairos in the past decade, only five identified themselves as feminists.

We felt there are interesting implications here. First, though we read Kairos as a journal that is heavily influenced by feminist scholarship, the overwhelming majority of authors claim no explicit identification as a feminist scholar or writer. This may be because authors perceive the work of feminism as different from the work done by a journal focusing on rhetoric, technology, and pedagogy. Others may not consider themselves feminists regardless of the context.

That the majority of authors, 63%, chose not to provide their credentials is also noteworthy. Without surveying the authors it is impossible to say why this is so, but some authors may purposely omit their credentials in an effort to even the balance of power between themselves and junior colleagues or graduate or undergraduate student co-authors or research participants. For others, this omission may be because a general assumption exists that one's credentials are easily accessible with a quick Google search.

[Editor's addendum: Although it is not part of our submission guidelines, Kairos has consistently asked authors to refrain from including their credentials in biographies, because that information changes quickly in academia, particularly in terms of rank or institutional affiliation. Indeed, in our ghost copy-editing process for this issue, Editor Ball removed several instances of rank, and also gender, from the author biographies of this webtext. This was done particularly in bios of students who self-identified as "getting ready to graduate," referring most likely to May 2014. She offers this bit of information about Kairos author ranks: During the journal's metadata project of 2011, we researched all authors' ranks and discovered that the numbers were roughly split down the middle (~50%/50%) between untenured authors (i.e., undergraduate student, graduate student, independent scholar, unaffiliated scholar, nontenure-track lecturer, academic staff, or tenure-track scholar) and tenured authors (i.e., at the associate or full levels). We did discuss whether to mine metadata for gender during that project but felt we had to draw the line at collecting too much data in order to complete the project at hand—perhaps an oversight that this review is having us reconsider.]

10 years of webtexts

8.1 Issues of New Media

(Spring 2003)

The works in this issue of Kairos focused on new media's roles in academia; specifically, how new technologies impact academic understanding both inside and outside of the classroom. All works focused on this idea of challenging how academic writing sometimes does not complement changes in technology. "Violence of Text: An Online Publishing Exercise" is an excellent example of a text that challenged the systems of power and norms. This piece challenged the idea that academic papers are the best way to articulate academic findings. The authors feared that "humanities academics have a limited set of literacies or competencies when it comes to reading or accommodating new media objects, largely because the majority of academic content in these new environments mirrors and privileges traditional paradigms." In order to challenge these limits, the authors proposed that scholars use new technologies to perform ideas instead of describing them.

8.2 Computers and Writing in 2003

(Fall 2003)

This issue covered webtexts presented at the Computer and Writing Conference held at Purdue University in 2003. The topics ranged from the software industry's and students' take on teaching and learning Flash, to how teaching composition online provides a unique experience that may be more helpful to students than face-to-face training. Overall, the majority of the webtexts concentrated on the voices of the scholar as well as the concerns of the participant, although they weren't always necessarily voiced. Most webtexts also challenged norms of how people teach writing. One webtext in particular, "Year Zero: Faciality… Redux!" by Victor Vitanza, was more concerned with changing how we view the world as a society. Keeping with the theme of writing, Vitanza used language as an example of how society should challenge norms and how so much of life is based on aesthetics—that is, things that matter on the surface, like gender.

9.1 The Rhetoric and Pedagogy of Portable Technologies

(Fall 2004)

This issue was a mixed bag when it comes to feminist themes. Some webtexts did a great job of challenging existing power structures by arguing against the move towards class blogs—such as in "When Blogging Goes Bad"—or including the voice of participants when quoting students' frustrations with the lack of face-to-face interactions in computer classrooms on "Fashioning the Emperor's New Clothes." One standout piece was Melissa Graham Meeks's "Wireless Laptop Classrooms: Sketching Social and Material Spaces." Meeks identified her position and bias as a scholar by recognizing her background as both a student and instructor in wireless classrooms and how that impacted her worldview. Her piece was embodied in that she used her own experiences and frustrations in the classroom as real life examples for her arguments.

9.2 Writing in Globalization

(Spring 2005)

Many perspectives that challenged notions of the traditional writing classroom can be found in this issue, which included validating approaches like spam as teachable moments and encouraging electronic portfolios to bridge the gap between school and the work world. The standout moment for fans of feminist scholarship is Achariya Tanya Rezack's "Deleting Teachers' Fears: Audio/Visual ICTs and the Classroom." Another in a lineage of Kairos webtexts encouraging faculty to push past their comfort zones, this piece embodied the voice of the author in an accessible tone and use of personal pronouns and allowed us to see the writer performing the technological intervention she proposed. Rezack's webtext also challenged the norms of the 2004 composition classroom by grappling with how to successfully embed technology.

10.1 The Intersections of Online Writing Spaces, Rhetorical Theory, and the Composition Classroom

(Fall 2005)

Ideas and strategies for incorporating modern technology into the writing classroom were at the heart of this issue. The move from traditional classrooms to the technology-rich spaces many of us occupy now were validated in these 2005 texts. The suggested inclusion of more technology in writing classrooms was intended to offer students deeper engagement in their learning. A particularly well-written example of this call to action comes in "Why Teach Digital Writing." The five authors, members of the Wide Research Center at Michigan State, encouraged students and professors to learn how technology could be an asset to their learning. This piece embodied the voices of the authors through advice based on the experiences of the authors and their students. This webtext strongly challenged the norms of a traditional classroom and validated what was still a somewhat revolutionary idea for writing pedagogy.

10.2 New Writing and Computer Technologies

(Spring 2006)

This issue of Kairos touches on a number of feminist approaches to pedagogy. The webtexts in this edition discuss connecting new media technology and composition, particularly in the classroom. The professors and scholars in this webtext implement multimodal representations of their work, notably Madeleine Sorapure's "Between Modes: Assessing Student New Media Compositions." This webtext and several others discussed evaluating and facilitating students' work in digital composition and research. Marshall Kitchen's pedagogy project empowered students and challenged societal norms by encouraging first-year students to independently research video games' representation of race and gender. Similarly, Robert Samuels' student webzines challenged systems of power by encouraging students to address issues in higher education. And, South African and North American academics shared cultures and addressed their personal experiences and positionality. The scholars were embodied and voiced when the political became personal. The teachers built a virtual community, collaborated between their classes with a focus on ubuntu, "hospitality and humanity," and validated their different educational experiences.

11.1 10th Anniversary, Part 1

(Fall 2006)

The first half of a 10th anniversary celebration that stretched into 11.2, this edition offered a look ahead for the journal and was written by co-editors Cheryl Ball and Beth Hewett. It therefore embodied both the writers and the journal. The edition considered the identity of the journal in terms of its power to challenge systems of power in the academy and the journal's own positionality. Other pieces offered reflection rooted in the voiced personal experience of editor Doug Eyman and a nontraditional multimodal journey through the archives that challenged the norms of reader path and academic writing. "Kairos and Graduate Student Professionalization" is an exemplar of reflection in that it was an embodied narrative of a student editor at the journal that validated the often undervalued role of mentorship in the field. Written by a relative newcomer to the field, the multimodal rollover image navigation for the piece offered a nice experience in an academic webtext and empowered the voices of students not heard often enough.

11.2 10th Anniversary, Part 2

(Spring 2007)

The special 10th anniversary issue embraced the feminist tenet of reflection and offered New Year's inspired resolutions that situated the journal in its kairotic moment and amidst other scholarly journals. Readers seeking out examples of feminist rhetoric will find lots to admire in Beth Brunk-Chavez and Shawn J. Miller's investigation of the power of shared digital spaces and in Xiaoye You's discussion of critical computer literacy in the ESL classroom and its related ability to offer students voice and agency. Catherine Gouge's "Writing Technologies and the Technologies of Writing: Designing a Web-Based Writing Course" offered an embodied view of programmatic design that was aware of positionality of both the author and the writing program being described. Particularly impressive was that the piece validated multiple experiences and subject positions by calling attention to issues like gender, socioeconomic status, and other issues impacting access to technologies.

11.3: Classical Rhetoric and Digital Communication

(Summer 2007, Special Issue)

A fusion of classical rhetoric and digital communication, this issue of Kairos aimed to highlight the progressive integration of technology into the discipline of rhetoric. "The Classical Trivium: A Heuristic and Heuretic for New Media and Digital Communication Studies" voiced the participant by inviting readers to interact with the webtext, which was housed on a wiki. "Who's Writing? Aristotelian Ethos and the Author Position in Digital Poetics" gave voice to the scholar by validating the experiences of authors. "iRhetoric Placeshifting: A New Media Approach to Teaching the Classical Rhetoric Course" challenged systems of power by considering adult learners in an online rhetoric class. Perhaps most interesting in light of our own attempt to re-map this journal as a feminist space, Paul Prior et. al's "Re-situating and Re-mediating the Canons: A Cultural–Historical Remapping of Rhetorical Activity" used a multi-voiced, multimodal format to track the way that the rhetorical canon has evolved over time.

12.1 Digital Scholarship

(Fall 2007)

This Digital Scholarship issue was concerned with answering the question, "where does my multimodal scholarship fit in the academic world?" Steven D. Krause answered the question directly with his piece, "Where Do I Put This on My CV? Considering the Value of Self-Published Websites - Version 2.0," and Allison Brovey Warner challenged norms with her piece, "Constructing a Tool for Assessing Scholarly Webtexts." The most secretly feminist piece was Joe Moxley and Ryan Meehan's "Collaboration, Literacy, Authorship: Using Social Networking Tools to Engage the Wisdom of Teachers." Moxley and Meehan's piece pointed out that though educators are now aware of how important collaboration is in academia, they fail to incorporate it in the classroom through social media and other online tools. The piece included the authors' own voices with the constant use of "we" and is itself a collaborative work with two writers. The webtext was empowering for readers and ended with a bid for reader feedback.

12.2 Virtual Urbanism

(Spring 2008)

Creativity was the dominant voice in this issue. From interactive role-play in "Space, Time and Transfer in Virtual Case Environments" to audiophonic literature in "(just) words," the issue offered truly engaging multimodal texts. A standout was Alex Reid's "Tuning In: Infusing Networks Professional Writing Curricula," which exemplified feminist rhetoric. His webtext embodied feminist expressions while educating the reader without relying on overblown academicese. Reid demonstrated the benefits of multimodality within academic writing instruction. He recognized the positionality of power in using network media such as iTunes U within college composition. By focusing on a medium familiar to students, he chose to validate their experiences. Reid expressed that it was time for educators to embrace technological change and use it to develop broader communication skills within the academic sphere. This pushback against a slow-moving pedagogical mechanism challenged the systems of power.

12.3 Manifestos!

(Summer 2008, Special Issue)

The values and problems addressed within the Manifesto Issue intersected with many key terms our class included in our definition of feminism. As guest editors Scott Lloyd Dewitt and Cheryl Ball stated in their introduction, manifestos "call us to action and demand change." Similarly, feminism calls people to action and encourages change. The webtext within this issue that seemed to relate the most to feminism was Catherine C. Braun and Kenneth L. Gilbert's multimodal work entitled "This is Scholarship." In this webtext, Braun and Gilbert challenged the widely accepted viewpoint that print publications were inherently more valuable academically than digital publications. In challenging this norm, "This is Scholarship" validated more forms of scholarship and opened up the discourse for voices that may have previously been neglected or marginalized. It questioned ways of thinking that excluded scholars who chose digital publication over print and called academia out on its biased tendencies. Sometimes accepted systems require an upheaval in thinking. As promised by this issue's theme, "This is Scholarship" was definitely a call to action. It validated the need for a more flexible and inclusive definition of scholarship that included online scholarship.

13.1 New Design Debut

(Fall 2008)

This issue offered many ideas and topics that both challenged and argued for traditional classroom writing and explored the pros and cons of learning via digital and webtextual writing. Of particular interest to feminist scholarship was the piece "Pulling the Difference: Re-envisioning Journals' Negotiations of New Media Scholarship." This piece revisited earlier arguments the author leveled regarding Computers and Composition's use of print in favor of Kairos's pioneering of digital text. The piece embodied the voice of the author by acknowledging previous arguments and what specifically happened in a decade to make her change the belief that print is less effective and innovative than webtexts. In this sense, the webtext challenged the norms of the scholar's own opinion of print versus webtext. The author, Patricia Webb Boyd, validated multiple ways of "doing scholarship" by recounting her personal research experiences, such as her attempts to Google the word "cyber" and challenged the historical definition of the term and what it meant to both journals.

13.2 Open Issue

(Spring 2009)

This issue included five different webtexts, all multimodal in individual ways. Of the five pieces in this issue, the most substantial was entitled "Productive Mess: First-Year Composition Takes the University's Agonism Online." In this piece, researchers looked at university freshmen who participated in an online class, as well as their struggles and triumphs throughout the process. This webtext gave voice to the students who might otherwise remain unheard in scholarship. Two videos are also included in this issue as well as a digital media map, which increased its accessibility to multiple types of readers.

14.1 Open Issue

(Fall 2009)

This issue expressed many different opinions and views on writing, rhetoric, and emerging technologies. "The Converging Literacies Center: An Integrated Model for Writing Programs" was an interesting example of scholarship with a feminist bent as the multimodal piece worked to integrate all different types of writers and support twenty-first century literacies. Other relevant webtexts included "Working with Wikis in Writing-Intensive Classes," as it not only incorporated several different types of writers, but also worked to validate their experiences and give participants a voice in the piece. Finally, "Resolution in 60 Seconds," a film by Hugh Burns, also worked to empower writers and embrace National Day on Writing with just a sixty-second clip.

14.2 Un/Defining Digital Scholarship

(Spring 2010)

As suggested in the issue title, this edition offered an important discussion of ways to define and validate digital scholarship. The webtexts included were a unique collection of nontraditional scholarly webtexts, including an interactive visual argument and a fascinating slideshow fiction, "Custom Orthotics Changed My Life." Choosing the best example of feminist rhetoric was a challenge in this issue and readers will find much to relate to in pieces that challenged systems of power related to academic scholarship. In particular, bonnie kyburz's "i'm like... professional" blended a timely topic with an embodied writerly voice in a unique multimodal composing space. This film included the voices of participants in the form of feedback by both fans and detractors of DIY video projects. This webtext was also particularly impressive in its ability to empower multiple ways of being when it came to scholarship and digital media use, in that the author openly embraced the messiness and imperfection of this project.

14.3 dot mil: Rhetoric, Technology, and Military

(Summer 2010, Special Issue)

In this special issue composed solely of pieces that pertain to the military, readers could find topics regarding the digital challenge to the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy to how the military is integrated into daily Israeli life from writing to commerce. A piece of possible feminist rhetoric would certainly be Paige Paquette and Mike Warren's "Telling War Stories: The Things They Carry." The piece challenged pedagogical practices by creating or inviting teachers to create online spaces for composition for military personnel. This webtext, about teaching deployed military personnel, really voiced the participant while also validating their experiences. Online composition allows for stories to surface that aren't subject to the limitations of the classroom. The issue's possible classification as feminist rhetoric came in the pedagogical practices that advocated to empower nontraditional students' classroom experiences.

15.1 Open Issue

(Fall 2010)

Though a relatively small issue, this edition included many examples of feminist rhetorics. In fact, two will be highlighted here. Daniel Anderson's "I'm a Map, I'm a Green Tree" is a multimodal video and textual expression of how people interact with technology and the world around them, and how these interactions translate into compositions. Anderson embodied the scholar by referring to himself as a part of a "we" throughout the text. The author also validated experiences and gave voice to the participants in his exploration of how individuals form their own connections with others (both things and people). Similarly, Drew Kopp and Sharon McKenzie Stevens' "Re-articulating the Mission and Work of Writing Programs with Digital Video" demonstrated several principles of feminist rhetorics. Their work actively challenged societal norms and systems of power by offering a new rhetorical learning style fostered through digital video. In doing so, the authors validated experiences and gave voice to the participant by increasing the accessibility of learning within writing programs. These scholars demonstrated an awareness of their own positionality within the field of rhetoric, and this allowed them to embody themselves as scholars in their work.

15.2 Memory, Family, Composition

(Spring 2011)

This issue brought unique perspectives on the valuable relationship between technology and family. The traditional view of technology as a digital medium where one disconnects from the real world and from people was challenged throughout this issue, as the focus more fully incorporated a dynamic relationship between technology and people, bringing connections where they could not have been otherwise. Out of the webtexts presented in this issue, Erin Anderson's "The Olive Project: An Oral History Project in Multiple Modes" stood out as the most feminist piece. Anderson focused on recovering the memory of her grandmother and expressing her voice as a participant and validating her experience as a woman who lived a full, long life. She took the three-hour long interview that she completed with her grandmother and expressed it in multiple modes that challenged standard narrative construction: in a three-minute compressed video with overlaying and complex images, with a nonlinear timeline that included pictures from her grandmother's life, and with audio clips from her interview.

16.1 (Re)mediating the Conversation: Undergraduate Scholars in Writing and Rhetoric (Fall 2011)

The topic of this issue as a whole empowered all ways of being and challenged systems of power and norms by opening up academic spaces of research journals to undergraduate students who tend to be excluded from the publication element of academia. These webtexts included several collaborative projects completed by faculty and their undergraduate research assistants, including an examination of the intersections of social networking and the classroom and an interrogation of how to write a webtext for publication. The webtext that stood out as the most representative of a feminist rhetoric was written solely by an undergraduate. Tara Kloeppel's "Anna Wintour: The Truth Behind the Bob" was written as a final project for a Feminist Rhetoric class, like ours. The webtext examined how Vogue editor Anna Wintour used different rhetorical strategies in order to position herself and Vogue as elite in the fashion industry. The multimodality of the webtext added to the message by helping the reader feel as if he or she was in the pages of a Vogue issue. Kloeppel also used the voice of the participant by using specific quotes and situations that validated this reading of Wintour's rhetorical strategies. Not only did this webtext challenge systems of power and norms by opening academia to undergraduates, but it also brought in traditionally feminine subjects, such as the fashion industry, that are too often excluded from academic research.

16.2 Open Issue

(Spring 2012)

Non-normative uses of technology were at the heart of this open issue and thus challenged norms in topic alone. Multimodality was essential to all of the webtexts, and the standout webtext in regards to feminist characteristics was "syncretism: mashup" by David J. Staley. The webtext defined syncretism at the bottom of the webtext and pulled the viewer in by scrolling through a number of pictures to learn more about syncretism and why it is important. The images were engaging and revealed that syncretism is a coming together of extremes and differences. This webtext might then be seen as validating other ways of being and empowering readers to view and understand an important new concept.

16.3 Spatial Praxes: Theories of Space, Place, and Pedagogy

(Summer 2012, Special Issue)

This issue examined writing and rhetoric as a spatial practice. The standout piece that best aligned with our definition of feminist rhetoric was the collaborative project (much like this one) "Space/Event/Movement: Reflections on a Spatial & Visual Rhetorics Graduate Course." This piece embodied the voice of the authors, and as a collaboration of 10 scholars, challenged the norms of traditional authorship. The webtext was approachable for all readers because it was multimodal; it used HTML, Prezis, and images. The authors were attuned to positionality, as there was a bio section with each author's professional information. The piece appeared in first person, which allowed for embodied narratives and validated experiences in the classroom as personal and also worthy of scholarly consideration. This piece was unique in its strong feminist influence with references to feminism both in the text itself and in the bibliographies where some of the authors self-identify as feminists.

17.1 Open Issue

(Fall 2012)

There were several good options in this issue for those interested in feminist rhetoric—from Rachel Parish's graphic novel that juxtaposed early feminist rhetorician Sappho with Socrates, to Claire Lauer's interview-intensive approach to new media scholarship that focused on teachers' lived experiences. The standout, though, was "The Movement of Composition: Dance and Writing." This nontraditional webtext empowered multiple ways of being via a multimodal video approach to scholarship. The one-minute video at the heart of the project challenged the norms of scholarship and offered a nonlinear text that validated experiences both physical and intellectual. The author also included a descriptive transcript for the video and with it an awareness of accessibility issues.

17.2 Open Issue

(Spring 2013)

Though brief, this edition offered much for feminist scholars to enjoy with its focus on the possibilities offered by technology. "MoMLA: From Gallery to Webtext" was a transcribed—and therefore accessibile—discussion of a gallery presented at the Modern Language Association conference that purposefully challenged traditional forms of scholarly production. Another webtext that highlighted the beneficial ways technology allows collaboration, "Virtual Teaming: Faculty Collaboration in Online Spaces" embodied and validated the experience of three authors who successfully teamed together (including one from this webtext!). Particular attention should be paid to "Writing a Professional Life on Facebook," which provided several choices for viewing, listening, or reading, but relied strongly on a 10-minute video to validate the possibility of living a professional and public life in a space marked both private and personal. The webtext's topic and narrative construction challenged the norms of technology use and the journal genre.

17.3 Multimodal Research Within/Across/Without Borders

(Summer 2013, Special Issue)

The five major webtexts in this issue shared the common goals of forwarding technology use to improve education and presenting different ways to teach. None of these webtexts identified as feminist per se, but all were multimodal, challenged norms of the classroom, and validated new ways of being and doing. The webtext that most closely resembles our definition of feminism was "Making Means at the Intersections: Developing a Digital Archive for Multimodal Research." The piece was concerned with accessibility, as it offered a brief video tutorial on using an interactive webpage and also embodied the authors, as each writer expressed their positionality and was given equal voice in the webtext.

18.1 Accessibility and Multimodal Composition

(Fall 2013)

This issue focused on how multimodality affects different ways of being, and how to empower those who find traditional multimodal approaches inaccessible. Some of the webtexts were "how to" guides on making multimodal presentations more accessible, with a focus on Prezi and ways to compose video on iPads. The webtext that was most representative of a feminist rhetoric is the collaborative piece "Multimodality in Motion: Disability & Kairotic Spaces". This webtext challenged the systems of power and norms that the magazine (whether intentionally or not) upholds and recommended how Kairos itself can become more accessible and empower all ways of being. The webtext had a blurb written by each of the contributors, effectively embodying the scholars. The webtext also spoke to how those with certain disabilities may be unable to experience the effects of webtexts in Kairos, thus giving voice to readers that might not otherwise be represented.