Attending to Subjectivity and Visualizing Dissent

Structuring Data to Visualize Situated Geographies

Why should we locate encounters and tweets that don't go viral or circulate widely? Studying viral tweets and hashtags is the dominant trend in rhetoric and writing studies scholarship as well as in other academic fields. While there are benefits to these kinds of studies, virality, especially in hashtag activism, is often, though not always, viewed as less impactful and significant than embodied protest. Although Twitter-based movements like #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, #OWS and the various hashtags employed during the Arab Spring uprisings certainly give credence to the idea that social media-based activism facilitates profound social, cultural, political, and legal consequences in the offline world, what is the significance of social media encounters and media that don't go viral or widely circulate? How does studying these communications provide rhetoric and writing studies with a more nuanced understanding of "rhetoric as it happens" in virtual and embodied spaces?

To explore these questions, I had to restructure the data I collected, and, as Catherine D'Ignazio (2017) and others have emphasized, examine my data collection and structuring choices and those made for me by technologies like Twitter and Tableau. Once I'd located an initial @DefendBoyleHts encounter in the large dataset, I began to separate out all of the @DefendBoyleHts tweets from the two million tweet collection. Then I collected other data types—like additional DBH tweets, Facebook posts, Instagram posts, and Youtube videos—and compiled primary and secondary research related to Boyle Heights's cultural history, particularly materials that focused on activism and art. I read numerous newspaper features, journal articles, and book excerpts, many highlighting the history of immigrant culture and Chicano activism in Boyle Heights. Boyle Heights was especially important to the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. Chicano mural art created there played an important role in uniting Chicano people locally and nationally, and murals play a continuing role in the cultural identity of the Boyle Heights neighborhood. Boyle Heights is no stranger to gentrification and development. Initially an enclave for nonwhite residents due to racism and racially restrictive real estate and lending practices, over the years Boyle Heights has been negatively affected by urban development efforts, like six highways, including two major interstates, that cut through the landscape and devalued properties. To better understand DBH’s embodied and digital resistance in Boyle Heights and in the Twittersphere, and the encounters and rhetoric associated with this circulation, I collected all @DefendBoyleHts tweets, which amounted to approximately 1,200 tweets and associated metadata.

Defend Boyle Heights is a grassroots activist coalition that has garnered considerable media attention from the Los Angeles Times (Miranda, 2018) and The New York Times (Medina, 2016) to Newsweek (Nazaryan, 2017). Mainstream media reporting typically characterizes DBH and gentrification resistance efforts in Cruz Medina and Octavio Pimentel's (2018) racial shorthand, often representing the group as violent Latinx protestors who vandalize art galleries and throw objects at gallery owners, using words like "radical," "militant," and "outspoken." This racial shorthand is on par with Medina and Pimenthal's observations of dominant media representation of activists as "thugs, looters, and anarchists." I first encountered DBH through a YouTube video linked in one of the tweets in my dataset, which I'd located, not by examining a retweet peak, but by looking into the less-frequent data in the original tweet line. The video shows DBH's first anti-gentrification protest, which was waged against PSSST Gallery, one of several galleries moving into the Anderson Row Warehouse District of Boyle Heights, Los Angeles. On May 14, 2016, DBH and other grassroots groups in Boyle Heights assembled in front of PSSST, projecting their own art on the outside wall of the gallery: a series of images, including a rose blooming, money falling from the sky, and then a screen-printed figure with the words PISS on PSST. In front of the gallery, protesters chanted, "El pueblo unido jamás será vencido!" (In English, "The people united will never be defeated.") This video is just one instance corresponding to an initial protest and then resurfacing in retweets and metaculture coverage, of how DBH moves in physical and digital spaces, generating social encounters and rhetoric that impacts incoming businesses, nonprofits, art galleries, and the working-class residents of this predominantly Latinx, immigrant neighborhood (see the Los Angeles Times “Mapping L.A.” project and U.S. Census data on Los Angeles County at Census Reporter).

This video and protest occurred in early 2016, shortly after I'd begun collecting tweets, and around the time that Defend Boyle Heights coalesced as an activist group, creating several public social media accounts and a blog. In their Twitter profile, @DefendBoyleHts described themselves as "an autonomous coalition committed to building community power against gentrification principally through direct action." At the time of this writing, their Twitter profile (1,578 followers) is often a vehicle used to link to various other online platforms: blog (unpublished number of subscribers), Facebook (9,322 likes and followers), and Instagram (7,898 followers). DBH's blog outlines the history of the group and offers documents associated with activist groups like mission statements, reports, principles of solidarity, and an explanation of their tactics.

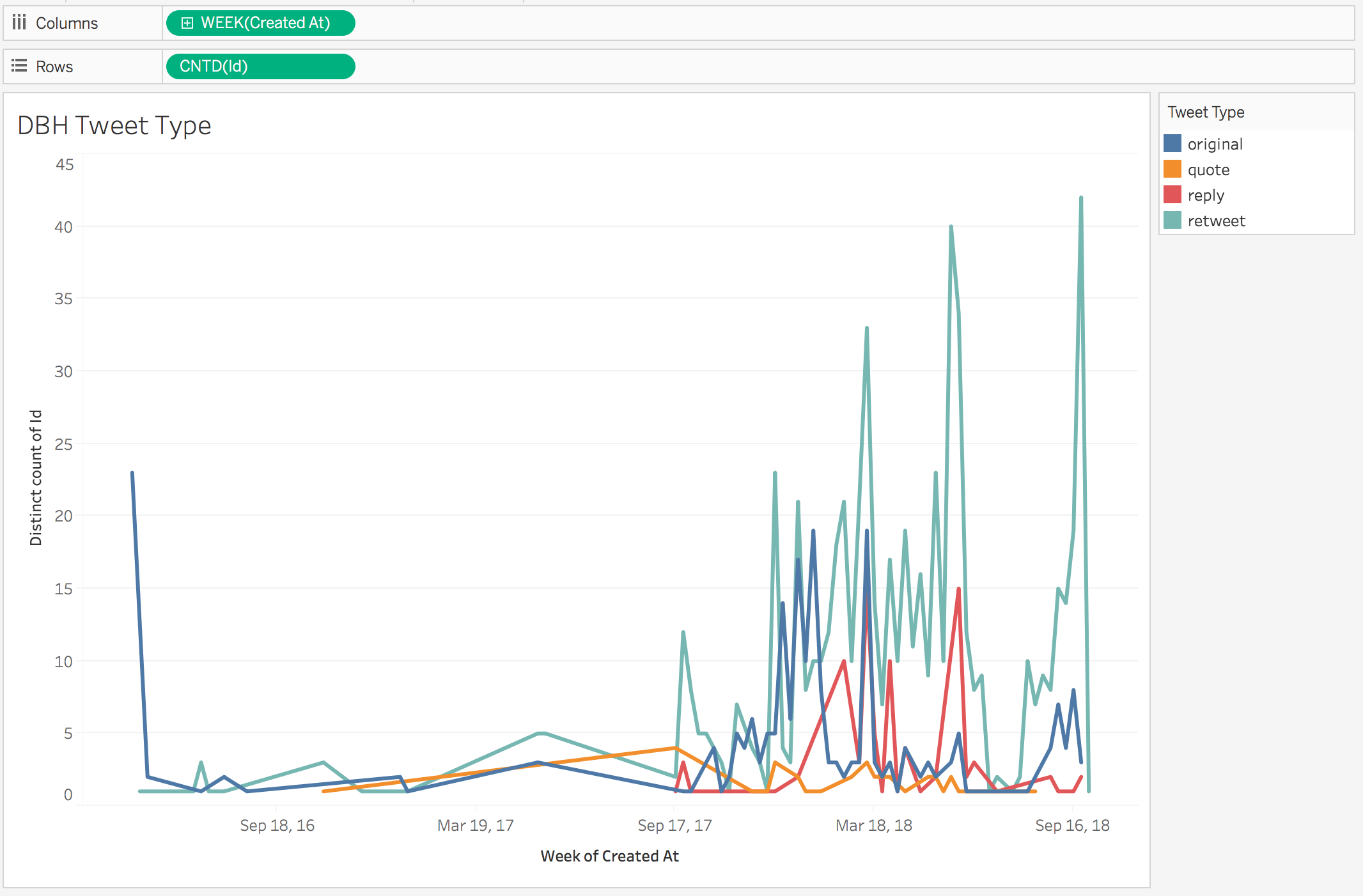

Initially, I tried the same Tableau techniques I'd used with the large dataset on the smaller DBH tweet collection. By doing so, I was able to identify key moments in their history and particularly energetic resistance through examining peaks of activity. For instance, @DefendBoyleHts Tweets from 2016 to 2018 (Figure 8) demonstrates that they became much more active on Twitter during their second year; however, these peaks aren't what we'd consider viral, which is why this activity is hidden in the two million tweet visualizations. Because DBH is the author of most of the tweets in this smaller dataset, rather than visualizing viral retweeting, Tableau frequency measures most often correspond to energetic grassroots activism, perhaps coordinating a physical protest of an art gallery, or tweeting at gallery owners, developers, or politicians as a way to exert public pressure onto these figures and their decision-making related to gentrification.

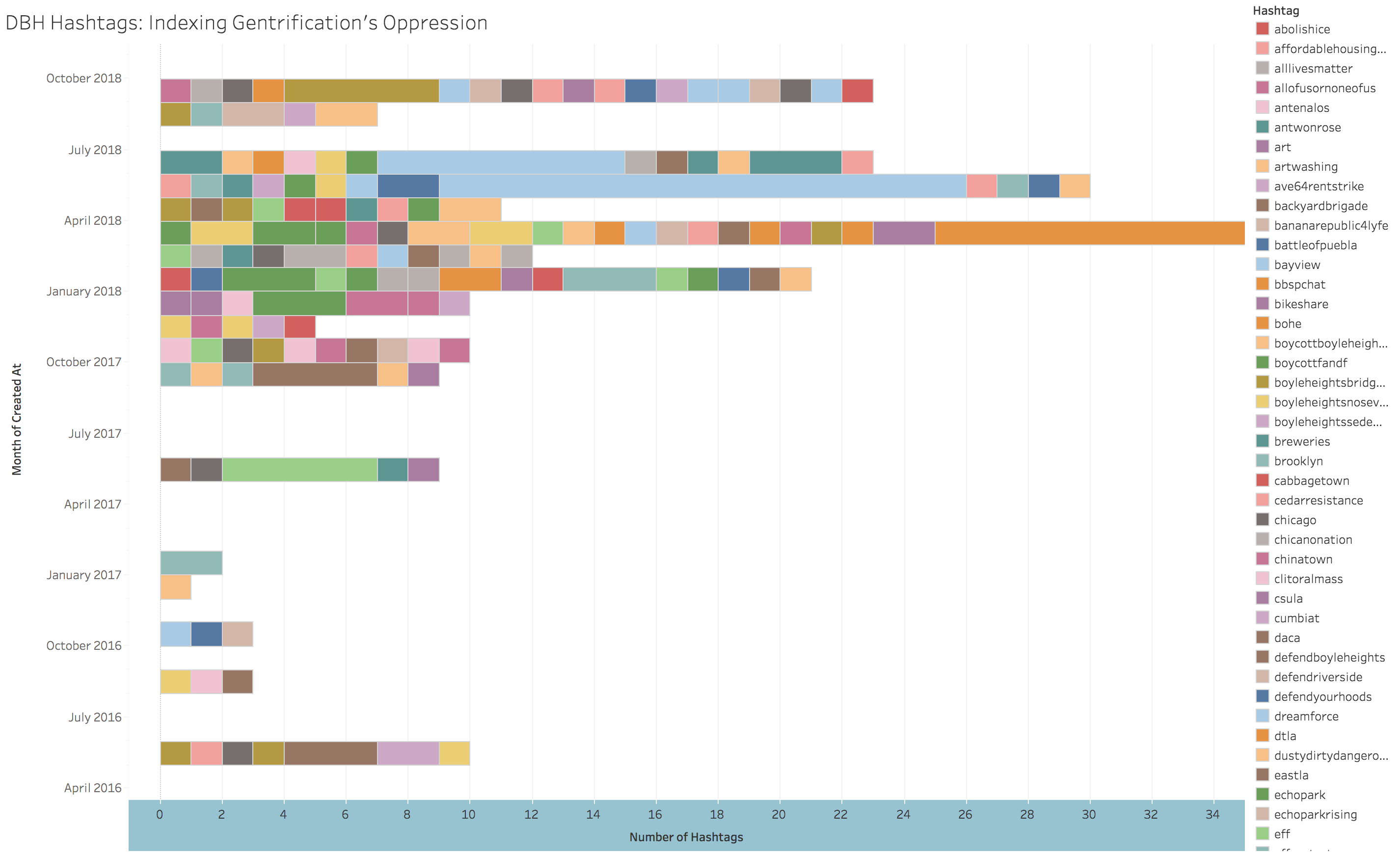

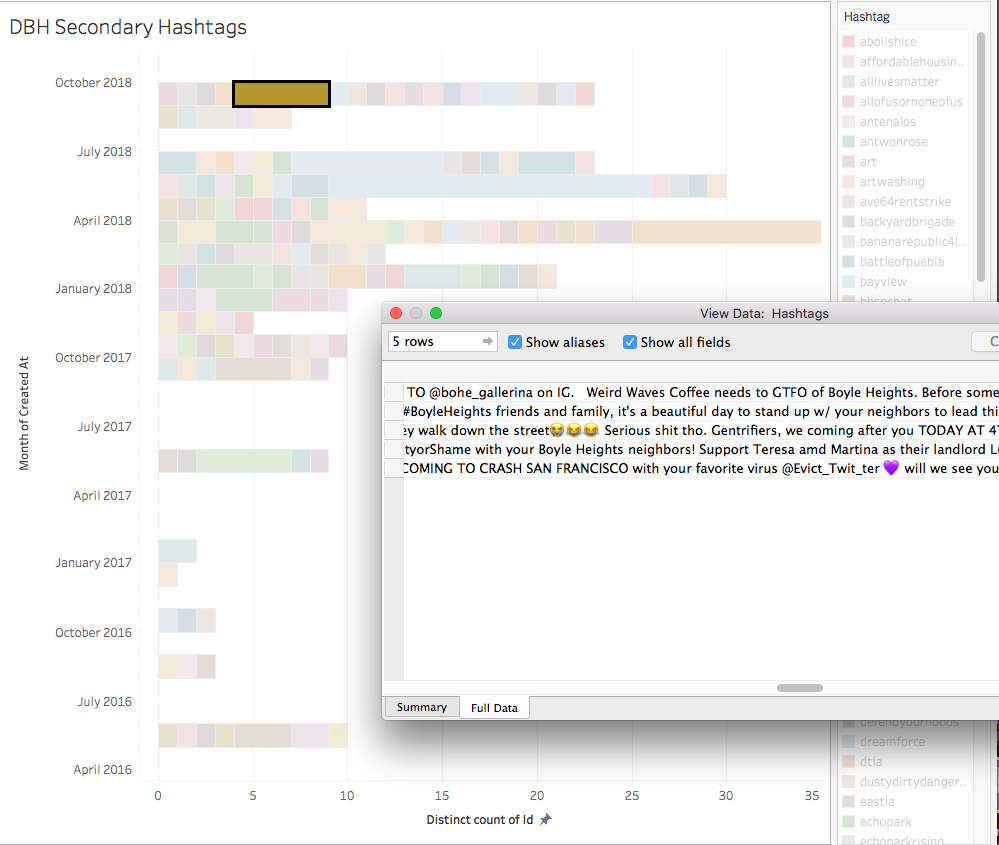

@DefendBoyleHts is not associated with any one hashtag but often uses numerous hashtags to connect with a variety of issues, users, and affects, demonstrating the nuanced connection between gentrification and other elements of systemic racism, like police brutality and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainment of undocumented citizens. A chart plotting secondary hashtags (Figure 9, below) visualizes the diversity of issues, groups, and affects that DBH brings into anti-gentrification encounters through the use of hashtags. Closer inspection of the underlying data often shows these hashtags connect to locations and targeted direct actions as well as to activists and ordinary citizens, both locally and over widely separated geographical distance (Figure 10, below). In another example, the larger pale blue area of the graph that corresponds to #FuckYourFlips, most prevalently in May and June of 2018, contains tweets by DBH and widely geographically separated users who engage in direct action against gentrification by removing "We buy houses for cash" and similar signs often appearing in historically undervalued neighborhoods and preying on financially vulnerable residents. #FuckYourFlips tweets often show videos and images of ordinary citizens removing such signs and calling on others to do so, both as an act of gentrification resistance in their local communities and as an act of solidarity with other poor and working-class communities fighting displacement. In the encounters connected to the underlying data, DBH often amplifies the activism of others, simultaneously urging others to participate and connecting to related advocacy groups like the LA Tenants Union, by retweeting, using the @ mention convention, and attaching numerous hashtags.