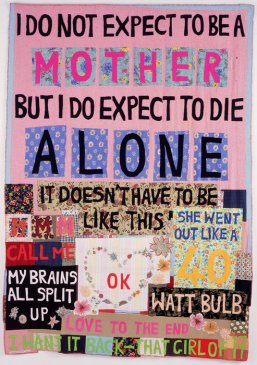

Large quilt with uneven capital lettering, in varying colors but primarily in black, appliqued on a background of pink and mismatched floral-print fabric swatches. Appliqued text reads: I do not expect to be a mother but i do expect to die alone; it doesn’t have to be like this; she went out like a 40 watt bulb; mmm; call me; my brains all split up; ok; love to the end; I want it back–that girl of 17.

This project had several sources of inspiration that each contributed to its development in different ways. First and foremost is my visual image inspiration, Tracey Emin’s (2002) I Do Not Expect To Be A Mother But I Do Expect to Die Alone. I have long been a fan of Emin’s raw and intimate art, which uses a wide variety of mediums and modes to express unchecked emotion and unfiltered truth. I found her work to be particularly well-suited to serve as a visual artifact rich with rhetorical meaning for transmodal interpretation. Sonja Foss (2004) defined a visual rhetoric artifact as “the purposive production or arrangement of colors, forms, and other elements to communicate with an audience” (p. 304). Thus, my first step was to begin analyzing the rhetorical significance of the physical and visual elements of Emin’s work. In this piece, Emin uses a quilt–a medium that immediately conjures associations with women’s social groups and relationships, as well as traditions passed down from one generation to another. Within this quilt, her bold and stark text is confrontational in its consideration of a woman’s role and identity as a mother (or not), as a girl, as a lover. The fragmented texts and uneven, patchy construction of the quilt suggest conflict, confusion, and struggle. The colors and patterns–dominated primarily by fields of pink and floral patterns–again tie that conflict back to femininity and a woman’s identity.

Emin’s (2002) quilt is essential to the content of my project. I determined I would use her exact fragments of text in my work directly, repurposing them to emphasize their relevance not just to one woman’s statement, but to many women’s conceptions of their identities and conversations among each other. This is how the subject of my audio drama came into being; I sought to use both the words and the visual rhetorical themes from Emin’s quilt to construct a conversation among women, discussing issues of identity between and among generations, specifically considering issues of motherhood and sexuality.

The second piece that inspired this audio drama was Erin Anderson’s (2014) Coerced Confessions. This exciting work coerces actors to unwittingly perform famous public confessions by rearranging the text into a new speech, which is then recorded and remixed back into the original confession. What I found particularly intriguing about Anderson’s project was the subject matter of the speeches constructed out of the confessional text, and how it was necessarily informed by the limited word choices available. For example, in the real confession of a mother who murdered her children, which then becomes a Dear John letter, both texts that deal with uncontrollable emotions and complicated relationships. Anderson’s work greatly inspired the process of constructing my audio drama, as I too wanted to maintain some elements from Emin’s piece while placing them in a new context.

Ann Berthoff has said

from artists we can learn even more fundamental truths about forming—that you don’t begin at the beginning, that intention and structure are dialectically related, that the search for limits is itself heuristic, that form emerges from chaos, that you say in order to discover what you mean, that you invent in order to understand and so on. (as cited in Palmeri, 2012, pp. 39-40)

This idea absolutely informed the process of building the text for my audio piece. Drawing inspiration from artists Emin (2002) and Anderson (2014), I began with a sort of formless chaos of ideas, and let the shape they took guide my composition. To begin, I chopped up the various fragments of text from Emin’s quilt, keeping chunks of text together based on their visual representation in the quilt (keeping like colors and patterns together, for the most part). I pushed the chunks of text around, looking for new connections and jotting down notes that might link one piece with the next. As Jason Palmeri (2012) pointed out in his work on creative translation, “even when writers are planning verbally, they are not necessarily thinking in prose-like sentences” (p. 33). I wrote the script for my audio drama in this way–restructuring and building around those fragments, linking together concepts and phrases, and eventually constructing an entirely new work while being sure to include all of the quilt’s text in my final product. This process forced me to think in different ways about the things Emin is saying and the language she is using. It prompted me to ask myself questions like: “Why else might this woman be talking about a 40 watt bulb? Or brains split up on the pavement? Or what she does and does not expect to be?” This is where I think the core of this project really came together; my speaking character is a very different person from Tracey Emin’s speaker, but they still use the same language. They share a kind of conceptual dialect wherein they consider the same ideas of motherhood, death, youth, and love, despite their different perspectives and opinions on those topics.

The third and final inspiration for this work–as well as its eponym–was the 1974 Francis Ford Coppola film “The Conversation.” In this film, a surveillance expert becomes obsessed with a conversation he’s been hired to record, though he doesn’t know why he’s been hired or the context of the conversation. Many of the things said in the conversation are vague and ambiguous, and may be interpreted a number of different ways depending on the context one imagines. This is what inspired the final form of my audio drama, a one-sided phone call. I was interested in the idea of the overheard conversation, and how a listener builds meaning in the absence of information. In my project, two pieces of information are missing: context (all information is contained in this one phone call) and, of course, the other side of the conversation. This aspect of the project felt the most experimental to me; I was curious to see how meaning-making would happen for the listener, how much of my meaning they would infer, and how much of their own they would apply. It was difficult to guess–knowing myself what I imagined the other side of the conversation to be–if other people would hear the story the same way that I wrote it. How much of the information is made clear? What do I expect you to assume?

Voice was a significant concern for me in the recording phase of this project, as I chose to use my own voice as that of the speaker. Theo van Leeuwen (1999) said of voice:

A voice is never only high or low, or only soft or loud, or only tense or lax. The impression it makes derives from the way such features are combined, from the voice being soft and low and lax and breathy, for instance–and of course also from the context in which the voice is used–from who uses it, to whom, for what purpose, and so on. (pp. 129-30)

For this reason, some aspects of the role voice plays in my work were in my control–becoming soft and lax in moments of reflection, or tense and loud in defensiveness–but other aspects of my voice that are outside of my control might also influence the perception of the speaking character in the final work. In particular, while I was initially anxious that my voice would not adequately convey the character’s age as I imagined it–at least 10 years older than I am–I was surprisingly pleased when I was right. Listeners did initially think the speaker was referring to a sister or roommate rather than a daughter, very likely as a result of my youthful voice, but as the phone call progressed they were forced to adjust that assumption when more information made the relationships clearer. I was glad to see this effect; I think it creates an experience for the listener that is similar to both Anderson’s (2014) Confessions and Coppola’s film. The audience must attempt to imagine a context for the phone call. They are trying to build meaning with limited information, so while they are apt to maintain important themes and concepts, their specific constructions may differ significantly from the piece I wrote.

I think what I learned the most about in the development of this project are issues of audience. In previous projects, I have focused primarily on how to convey information to an audience in a way that makes my ideas and intentions clear. Controlling the message as much as possible, through manipulation of mode and medium, seemed to be the primary objective. My conception of audience was something like what Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford (1984) referred to as “invoked”; I envisioned my audience and their understanding of my work as something within my control, constructing my text as “a vision which they [writers] hope readers will actively come to share as they read the text-by using all the resources of language available to them to establish a broad, and ideally coherent, range of cues for the reader” (Ede & Lunsford, 1984, p. 167). In this project, however, I discovered that there can be a great deal of value in letting go of that control and leaving room for an audience to construct their own meanings. Many of the women I shared this piece with imagined themselves in conversation with their own mothers (or sisters or friends) and brought ideas about those relationships into dialogue with the text I created. This is a much richer and more personally meaningful experience than if I had created a more tightly scripted (and perhaps better acted) dialogue. I used sound effects to provoke a particular genre–a phone call–but within those boundaries I expect and hope the listener will engage with the work to build meaning of their own design, though I’ve provided the scaffolding. Even later in the project, when some of my own intentions become clear, the process of questioning and imagining that the listener has undergone will ideally raise questions for them about their own assumptions and experiences. Coming out of this project and moving forward, I expect to continue thinking about composition as a dialogue with and an invitation to the audience, and not as a tightly controlled message, cast off into the world like a note in a bottle.

Audio Assets

Athenspublic. (2015). open-door-and-shut [Audio file]. Freesound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/athenspublic/sounds/266767/

Robinhood76. (2010). 01592 dialing phone number [Audio file]. Freesound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Robinhood76/sounds/94933/

Omar Alvarado. (2014). A000008 [Audio file]. Freesound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Omar%20Alvarado/sounds/251539/

Acclivity. (2006). DialingTone [Audio file]. Freesound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/acclivity/sounds/24735/

Image Asset

Emin, Tracey. (2002). I do not expect to be a mother but I do expect to die alone [Photograph]. Open College of the Arts. Retrieved from http://weareoca.com/fine_art/tracey-emin-love-is-what-you-want/